Deprecated: trim(): Passing null to parameter #1 ($string) of type string is deprecated in

/home/aoiusa/public_html/wp-content/plugins/sexybookmarks/public.php on line

388

Deprecated: trim(): Passing null to parameter #1 ($string) of type string is deprecated in

/home/aoiusa/public_html/wp-content/plugins/sexybookmarks/public.php on line

394

Deprecated: trim(): Passing null to parameter #1 ($string) of type string is deprecated in

/home/aoiusa/public_html/wp-content/plugins/sexybookmarks/public.php on line

400

Metropolitan Hilarion

Source: Catholic University of America

Talk given February 9, 2011 at Catholic University of America in Washington, D.C.

Mr. President, esteemed members of the Academic Senate, professors, teachers, students, dear friends!

First of all, permit me to express my profound gratitude for this invitation. It is a great honour for me to be within the walls of the Catholic University of America once again and to be addressing you. I was last here five years ago and at that time I spoke on Orthodox-Catholic relations. But today you have invited me in my dual capacity of churchman and a representative of culture. Acknowledging that I am not only a hierarch of the Russian Orthodox Church but also a composer, you have asked me to address you on the connection between music and faith as experienced by past and contemporary composers as well as by myself.

Music and Faith

I would like to begin with a thought on the relationship between music and creativity. I am convinced that culture and creativity can enhance faith, but they can hinder it too. The artist, composer, writer and representative of any creative profession, can, through his artistry, glorify the Creator. If creativity is dedicated to God, if the creative person puts his efforts into serving people, if he preaches lofty spiritual ideals, then his activity may aid his own salvation and that of thousands around him. If, however, the aim of creativity is to assert one’s own ego, if the creative process is governed by egotistical or mercenary intentions, if the artist, through his art, propagates anti-spiritual, anti-God or anti-human values, then his work may be destructive for both himself and for those about him.

We are familiar with Fr. Pavel Florensky’s view that ‘culture’ comes from the notion of ‘cult.’ We may add that culture, when divorced from cult, is in fact opposed to cult (in the broad sense of the word) and forfeits the right to be called culture. Genuine art is that which serves God either directly or indirectly. The music of Bach – though not always intended for worship – is clearly dedicated to God. The works of Beethoven and Brahms may not directly praise God, yet they are capable of elevating the human person morally and educating him spiritually. And this means – admittedly indirectly – that they also serve God.

Culture can be the bearer of Christian piety. In Russia during the Soviet years when religious literature was inaccessible, people learnt about God from the works of the Russian classics. It was impossible to buy or find in a library the works of St. Isaac the Syrian, yet we did have access to the writings of the elder Zossima in The Brothers Karamazov, which were inspired by the works of St. Isaac. Russian literature, art and music of the nineteenth century, albeit secular in form, preserved a deep inner link with its original religious underpinnings. And nineteenth-century Russian culture throughout the Soviet period fulfilled the mission which, in normal circumstances, would have been the work of the Church.

Now that religious persecution has ceased, the Church has entered the arena of freedom: there are no obstacles to her mission. A wall, artificially constructed in Soviet times, isolated the Church from culture. But now that it is no more. Church ministers are free to co-operate closely with people from the world of the arts and culture in order to enlighten the world. Church, culture and art share a common missionary field and undertake the joint task of spreading enlightenment.

J. S. Bach

I would now like to pause and reflect on certain composers whose works exhibit a combination of organic, creative inspiration with deep religious faith. I find the most obvious illustration of this mutuality in the creative work and indeed the destiny of Johann Sebastian Bach. Bach is a colossus; his music contains a universal element that is all-embracing. In his monumental works he manages to unite magnificent and unsurpassed compositional skill with rare diversity, melodic beauty and a truly profound spirituality. Even Bach’s secular music is permeated by a sense of love for God, of standing in God’s presence, of awe before Him.

Bach is a universal Christian phenomenon. His music transcends confessional boundaries; it is ecumenical in the original sense of the word, for it belongs to the world as a whole and to each citizen separately. We may call Bach an ‘orthodox’ composer in the original, literal sense of the Greek word ortho-doxos for throughout his life he learnt how to glorify God rightly. Invariably he adorned his musical manuscripts with the words Soli Deo Gloria (‘Glory to the One God’) or Jesu, juva (‘Help, O Jesus’). These expressions were for him not merely verbal formulae but a confession of faith that ran through all of his compositions. For Bach, music was worship of God. He was truly ‘catholic,’ again in the original understanding of the Greek word katholikos, meaning ‘universal,’ or ‘all-embracing,’ for he perceived the Church as a universal organism, as a common doxology directed towards God. Furthermore, he believed his music to be but a single voice in the cosmic choir that praises God’s glory. And of course, throughout his life Bach remained a true son of his native Lutheran Church. Albeit, as Albert Schweitzer noted, Bach’s true religion was not even orthodox Lutheranism but mysticism. His music is deeply mystical because it is based on an experience of prayer and ministry to God which transcends confessional boundaries and is the heritage of all humanity.

Bach’s personal religious experience was embodied in all of his works which, like holy icons, reflect the reality of human life but reveal it in an illumined and transfigured form.

Bach may have lived during the Baroque era, but his music did not succumb to the stylistic peculiarities of the time. As a composer, moreover, Bach developed in an antithetical direction to that taken by art in his day. His was an epoch characterized by culture’s headlong progression towards worldliness and humanism. Center stage became ever more occupied by the human person with his passions and vices, while less artistic space was reserved for God. Bach’s art was not ‘art’ in the conventional meaning of the word; it was not art for art’s sake. The cardinal difference between the art of antiquity and the Middle Ages on the one hand and modern art on the other is in the direction it takes: pre-Renaissance art was directed towards God, while modern art is orientated towards the human person. Bach stood at the frontier of these two inclinations, two world-views, two opposing concepts of art. And, of course, he remained a part of that culture which was rooted in tradition, in cult, in worship, in religion.

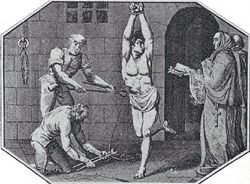

In Bach’s time the world had already begun to move towards the abyss of revolutionary chaos. This tendency swept over all of Europe from the end of the eighteenth century to the beginning of the twentieth. Forty years after his death, the French Revolution broke out. It was the first of a series of bloody coups which, conducted in the name of ‘human rights’, stole millions of human lives. And all of this was done for the sake of the human person who, once again, proclaimed himself to be, as in pagan antiquity, the ‘measure of all things.’ People began to forget God the Creator and Lord of the universe. In an age of revolutions people repeated the errors of their ancestors and began to construct, one after another, towers of Babel. And they fell – one after another –burying their architects under the ruins.

Bach remained unaffected by this process because his life flowed within a different perspective. While the culture of his age became more and more removed from cult, he entered ever more deeply into the depths of cult: the depths of prayerful contemplation. As the world was rapidly becoming humanized and de-Christianized and as philosophers achieved further refinement in formulating theories designed to bring happiness to the human race, Bach sang a hymn to God from the depths of his heart.

We citizens of the early twenty-first century can affirm that no upheaval could either shake our love for Bach’s music or our soul’s love for God. Bach’s oeuvre remains a rock against which the waves of the ‘sea of everyday affairs’ break.

The Development of Musical Art after Bach

Some opine that Bach was the last of the great religious composers and that sacred music in general, a legacy of antiquity, belongs exclusively to the past. Bach’s artistry indeed marked the threshold beyond which Western music distanced itself from its religious roots and took the path of secular development. Chronologically, the divorce between music and religion coincided with the Age of Enlightenment, and, having taken this radical step, musicians did not turn back until recently.

This does not mean that church compositions were abandoned in the Classical and Romantic periods. Far from it. Haydn, Mozart, Beethoven, Schubert and Brahms, to name but a few, wrote, for example, masterly settings of the mass and the requiem. After Bach, Brahms occupies second place in my list of favourite composers, and the third place is Beethoven’s.

I am very fond of the music of the Romantic period – of Schubert, Schumann, and others. Their works, however, bear a secular spirit even when the texts are religious. Undoubtedly their compositions are outstanding, highly emotive, and compelling: nevertheless they are fortified by a worldly air and by styles and forms foreign to associations of sanctity.

During the epochs of Impressionism and the Avant-garde, interest in anything to do with religion seems to have faded altogether. Avant-garde composers renounced the final elements that linked music to faith – the elements of harmony and of beauty as fundamental for musical creativity. Cacophony and disharmony became the constructive fabric with which musical works were built.

The mid-twentieth century saw music styles that turned from atonality and dissonance to aleatoric music and random sonorities, as heard in the works of Stockhausen and Ligeti or in those of John Cage who combined noise with silence. Important and groundbreaking was Cage’s piece entitled 4.33, which is nothing more than four minutes and thirty three seconds of complete silence, accompanied only by natural sounds (for example, the coughing of the audience in the auditorium). The appearance of this work in 1952 bore witness to the fact that the musical Avant-garde had completely exhausted itself – as if it had nothing more to say. Cage’s silence has little in common with the spiritual silence that burgeons from the depths of religious experience: his was simply a soundlessness which testified to the complete spiritual collapse of the musical Avant-garde.

Shostakovich and the Music of the Twentieth Century

It is my personal view that, in the history of twentieth-century music, there is only one composer who, in terms of talent and depth of inspired searching, comes close to Bach, and that is Shostakovich.

Bach’s music is dedicated to God and permeated by an ecclesiastical spirit. Shostakovich, on the other hand, lived at a different time and in a country where God and the Church were never spoken about openly. Yet at the same time all of his creative work reveals him to have been a believer. While he did not write church music and apparently did not attend Church services, his music nonetheless confirms that he felt deeply the disastrous nature of human existence without God and that he experienced profoundly the tragedy of modern society – a godless society – which had renounced its roots. This yearning for the Absolute, this longing for God, this thirst for truth prevails in all of his works – in his symphonies, quartets, preludes and fugues.

Shostakovich was someone who could not be broken by repression or condemnation by the powers that be. He always served the Truth. I believe that, like Dostoevsky, he was a great spiritual and moral example, whose voice, like that of a prophet, cried out in the wilderness. This voice, however, evoked and continues to evoke a response in the hearts of millions of people.

In the twentieth century, the art of music was wrenched from any religious association. Of course, throughout that century spiritual works were written, even in atheist Soviet Russia. Recently, music manuscripts of Nikolai Golovanov, chief conductor of the Bolshoi Theatre and a major figure in Soviet music, were discovered hidden in a drawer. We now know that throughout his entire life he composed sacred music which he knew he would never hear performed. Only today, half a century after his death, are we able to appreciate his works.

Many modern Western composers have written music to religious texts. It suffices to recall Stravinsky’s Symphony of Psalms, Bernstein’s Chichester Psalms, and the church music of Honneger, Hindemith and Messiaen.

The real return of composers to the sphere of faith, however, came only at the end of the twentieth century when, in place of discord, formless noise, aleatoric music and content-free silence, there appeared a newly devised harmony for the absolute spiritual silence of musical minimalism. What was least expected in musical art was a religious renaissance, but it was precisely this that surprised and satisfied the hopes of composers and the public. Following the possible and impossible innovations of the Avant-garde, characterized by abundant external effects within a glaring inner emptiness, audiences yearned for a music that united simplicity and profundity – a music simple in language and style but deep in content; a music which would stir people not so much by its strident themes and stark originality, not even one that would necessarily touch the soul, but a music that could transport one beyond the boundaries of earthly existence into communication with the world above.

It is not fortuitous that by the end of the twentieth century the West experienced an upsurge of interest in church music, in particular Gregorian chant. The Canto Gregoriano CD, recorded in 1993 by Spanish monks from the Abbey of Santo Domingo de Silos, became an international bestseller: by the beginning of the twenty-first century more than seven million copies had been sold. The producers could only guess as to what drove people to buy this disc and how the unison, monophonic tone of monastic plainchant surpassed in popularity the hits of the stars on the world stage.

Among living composers there are three in the West who enjoy considerable popularity – the Estonian Arvo Pärt, the Pole Henryk Miko?aj Górecki and the Englishman John Tavener. These composers vary in importance; they each write in an original style, each has own signature, his own characteristic, his uniquely recognizable modality. Nevertheless, much unites them both on the musical and the spiritual planes. They have all experienced the profound influence of faith and are ‘practicing’ Christians: Pärt and Tavener are Orthodox; Górecki is Catholic. Their remarkable productivity is permeated by the motif of religion, replete with deep spiritual content and inextricably linked to the liturgical tradition.

Arvo Pärt

Arvo Pärt is a composer whose visionary work is religiously motivated by the language of his music, rooted as it is in church tradition. Pärt is not only a faithful Orthodox Christian, but also a committed church man who lives an intense prayer and spiritual life. The abundance of his inner spiritual experience acquired in the sacramental life of the Church is fully reflected in his music which is sacred and ecclesiastical both in form and content.

Arvo Pärt’s genius and destiny are characteristic of his era. He began writing in the 1960s as an avant-garde composer working in serial techniques. In the 1970s, withdrawing from composition in search of a personal style, he undertook a study of early polyphony. The period of his voluntary silence and seclusion ended in 1976 when he wrote Für Alina for piano and Trivium for organ: his first pieces in a new self-made compositional technique which he labeled “tintinnabulation” (from the Latin tintinnabulum, a bell). In 1977-78 these pieces were followed by Fratres, Cantus in Memory of Benjamin Britten, Tabula Rasa, Arbos, Summa, and Spiegel im Spiegel.

The “tintinnabulation” style, which aimed at utter simplicity in its musical dialectic, is based on the consonance of thirds and developed from the musical minimalism typical of postmodernism. Pärt believes that just one sound, one tonality, and one or two voices are enough to engage the listeners. “I work with simple material – the triad, the one tonality. The three notes of the triad are like bells. That is why I call it tintinnabulation,” explains the composer.

Such an explanation, however, will hardly assist us in understanding why Pärt’s music exerts so strong an impression on listeners, including those unfamiliar with classical music. It may be that the straightforwardness, the harmony and even the palpable monotony of Pärt’s music correspond to the spiritual search of contemporary man. Twenty-first century music lovers, weary of change and self-indulgence, find consolation and repose in these undemanding triads. The listener, having grown out of tranquility, acquires a desired inner calm through these gentle chords. Yearning for “angelic music,” he communes with the world above through this semblance of monody akin to the regularity of church services.

After his emigration from the Soviet Union in 1980, Pärt devoted himself to sacred music composition, but specifically for concert performance. Between 1980 and 1990 he wrote many pieces to accompany traditional Catholic texts, including St. John’s Passion, Te Deum, Stabat Mater, Magnificat, Miserere, Berliner Messe, and The Beatitudes. The influence of the Catholic tradition is evident in his use of the organ and orchestra along with chorus and an ensemble of soloists.

Since the early 1990s, the inspiration of Orthodox Church singing and the Orthodox spiritual tradition has become appreciable in Pärt’s oeuvre. He has produced many compositions on Orthodox texts, mostly for choir a capella, including Kanon Pokajanen (The Canon of Repentance) on verses by St. Andrew of Crete, I am the true vine and Triodion on the texts from the Lenten Triodion. His pieces for orchestra, such as Silouan’s Song for string orchestra, are also marked by a profound influence of Orthodoxy.

Personal acquaintance with the late Archimandrite Sophrony (Sakharov), disciple and biographer of St. Silouan, the greatly revered Athonite elder canonized by the Church, has exerted significant influence on Arvo Pärt. When he lived in the Soviet Union, Pärt met a well known father-confessor who advised him to abandon music and begin work as a church watchman. Following his emigration, Pärt, as yet an unknown composer, encountered Fr. Sophrony, who gave the opposite advice: “Continue to write music,” said Fr. Sophrony, “and the whole word will know you.” And indeed, this is precisely what happened.

In spite of his advanced years, Elder Sophrony maintained an interest in the artistic work of the composer and kept in touch with him. There is a photo of the elder with earphones listening to Pärt’s music. Arvo Pärt used to spend several months a year in a house near the Monastery of St. John the Baptist in Essex, Great Britain, founded by Archimandrite Sophrony. There he attended monastic worship every day.

Silouan’s Song is based on words by St. Silouan: “My soul yearns for the Lord and I tearfully seek him out. How am I not to seek thee? Thou didst seek me out first and granted that I may rejoice in thy Holy Spirit, and my soul loved thee. Thou dost see, O Lord, my sadness and my tears… If thou didst not bring me to thee through thy love, then I should not have sought thee as I now seek thee, yet thy Spirit granted that I may come to know thee, and my soul rejoiceth that thou art my God and Lord, and unto tears I yearn for thee…”

These words are not actually narrated in Pärt’s work, rather they seem to be hidden in the melody played by strings. The entire composition is imbued with profound longing for God: grief and yearning for Him. We are left with the impression that the violins and cellos sing songs to God, praise Him and pray to Him.

After the separation of secular and Church music in the Age of Enlightenment, composers seem to have lost the ability to compose in this fashion. Who would have imagined that at the dawn of the twenty-first century the best representatives of the art of music would bring this skill back to God, praising Him “with strings and pipe.”?

My Own Creative Work

Allow me tell you something of my own musical creative work, not because it is worthy of comparison with that of the aforementioned composers, but because the sponsors of my lecture asked me to do so.

My career as a composer has been somewhat strange and unconventional. On one occasion I intentionally abandoned music forever because I was caught between ministry to music and to the Church, so I chose the Church.

My life as a musician began when I was a young child. My parents discovered that I had perfect pitch and decided to send me to a specialist musical school. I began playing the piano at the age of three, and the violin at six. Composing started when I was twelve, and by the age of seventeen I graduated from the musical school’s composition class and entered the Moscow Conservatoire.

It was assumed that I would become a professional musician. However, I began to attend church as well as classes, and with every passing day the church attracted me more and more while music did so less and less. For some years my mind was not exactly divided, but I did ask myself where I should devote my life. Finally, I realized that I wanted to serve the Church most of all.

I was called up during my student years at the Conservatory and, having served in the army, became absolutely clear about devoting my life completely to God; so I took monastic vows. I felt then that I had broken my ties with music once and for all. Renunciation of the world was first of all the renunciation of music. I neither composed nor played musical instruments, nor even listened to recorded music.

I was then in my twentieth year and was possessed by a somewhat radical outlook. I had abandoned music, I imagined, forever. Still, man proposes, but God disposes. I became a priest and spent many years serving God and the Church. The period of radicalism was over, and I began to permit myself to listen to classical music, though I was not actively engaged in music making.

In 2006 something changed in me, and I began to compose again. This is how it happened. As ruling bishop of the Vienna diocese of the Russian Orthodox Church I was invited to a festival of Orthodox music in Moscow. A composition written by me twenty years before was on the program. Listening to my own music, something stirred inside me, and I began to compose again almost at once. Apparently, I had lacked some kind of outside impetus. So I returned to creative work. Musical themes and melodies began to proliferate of their own accord and with such speed that I scarcely managed to record them. At first I had no manuscript pages so I scored sheets of paper by hand in order to write down the notes. Before long I equipped myself with staff paper and later mastered a computer programme that allowed me to plot the notes and listen to my recorded music digitally. I wrote quickly, though at odd moments, as I had no special time slot devoted to composition. Some pieces were composed in planes or in airport waiting halls.

I composed The Divine Liturgy and later The All-Night Vigil in this way, as also the St. Matthew Passion, Christmas Oratorio and my latest, The Song of Ascent.

The Divine Liturgy was completed during the first decade of June 2006, when I took official flights from Budapest to Moscow and from Vienna to Geneva. Much music was composed en route: at the Moscow and Geneva airports, and on board a Moscow-Budapest plane. As a church minister I can never be indifferent to the quality of music used in church. I have heard many different choirs during my twenty years of service at God’s altar. Very seldom could singing at the Liturgy be deemed satisfactory. More often than not the sound interfered with prayer, rather than assist at it. In order to focus on prayer I had to distance myself from the choral performances. Typically a precentor would select hymns by different composers from different epochs, written in different styles. This resulted in conflict between the inner structure of the Liturgy as a single whole and the unrelated items being performed. Word and music were entirely disconnected. This is why I decided to compose a full-scale Liturgy for worship. I wanted to compose a kind of music that would not distract either the celebrant, the reader, or the worshippers, all of whom were praying at the divine services. My musical settings of the hymns in the Liturgy are simple, easily memorized, and bear a resemblance to common chant. Worshippers praying at the service and listening to this music would feel that they are hearing familiar sounds. There is nothing novel or strange that would distract the faithful. I followed the same principles in my All-Night Vigil.

The St. Matthew Passion is an attempt at an Orthodox reading of Christ’s passion. Among the forty-eight pieces in the composition there are four fugues for orchestra, four arias, numerous choruses and recitatives. Unlike Bach’s passions, there is no libretto, only the Gospel account which is narrated by a protodeacon in Russian and in a manner familiar in the Orthodox Church. In addition there are texts in Church Slavonic from divine services of Holy Week which are set to choral music. This Passion lasts for two hours and consists of four thematic movements, namely, the Mystical Supper, the Trial, the Crucifixion, and the Burial. Certain pieces in the third movement are performed by male voices and low stringed instruments (violas, cellos, and double-basses). According to some critics, this musical composition for choir and string orchestra is unprecedented in the Russian musical tradition. It follows Bach’s format except that it is filled with Orthodox content. It may well be the case that, to a certain extent, I managed as best as I could, and in all modesty, to make the dream of the great Russian composer, Mikhail Glinka, a reality, namely, to “marry” a Western fugue with Russian church singing. Certainly, it was a risky endeavor, but as this composition was not intended for church use, I thought I could allow myself the challenge. May the public judge how successful this is.

The Christmas Oratorio is shorter than the “St. Matthew Passion.” A musical drama, it lasts some seventy-five minutes and is based on the theme of movement from darkness to light, from the Old Testament to the New. The “Oratorio” begins with rather somber music, meant to guide the listener to the Old Testament. Since the Gospel texts of the Annunciation and the Nativity of Christ are narrated, boys’ voices are introduced. After this, choral and orchestra sections alternate with solo arias. The music is intended to illustrate the entire story of Christ’s Nativity. The composition ends with a jubilant finale in which the combined forces of the two choirs and the orchestra lead into a glorification of the Lord with the words “Glory to God in the highest.” I am pleased to recall that the world premiere of this composition took place at the Basilica of the National Shrine of the Immaculate Conception in Washington, DC. The Oratorio was performed at the Church of St. John the Baptist in Manhattan, New York, NY, on December 18 of the same year, and at Memorial Hall, Harvard University, on December 20.

My latest composition is called The Song of Ascent. It is a symphony for choir and orchestra and was composed during the course of a week in August 2008, when I was on a short holiday in Finland. The libretto is based on the texts of the last seven psalms in the Biblical Psalter. Two of them are called Song of Ascent in the Bible.

The psalm texts are extremely rich in content and they express a variety of emotional and spiritual experiences such as sorrow, repentance, tenderness, contrition of heart, joy and exultation. In this sense, the Psalter constitutes a universal collection of devotions in which all the fundamental conditions of the human soul flow into prayerful lamentations addressed to God. The symphony has five movements, each with its own drama. Its overriding theme lies in the ascent from the depths of despair to the heights of prayerful exultation to the rapturous praise of God. Written for a large orchestra, it consists of a string group, woodwind, brass instruments, percussion, harp, and organ. A mixed choir divided into men’s and women’s groups is placed on either side of the stage.

The premiere of The Song of Ascent took place at the Grand Hall of the Moscow Conservatory in November 2009. The symphony was also performed at the Vatican on 20 May 2010 in the presence of Benedict XVI, Pope of Rome. Carlo Ponti, son of the famous actress Sophia Loren, conducted the Russian National Orchestra and the Moscow Synodal Choir. After the performance, the Pope expressed heartfelt words about the music. He considered that the concert opened a window to the “soul of the Russian people and with it the Christian faith, both of which find extraordinary expression precisely in the Divine Liturgy and the liturgical singing that always accompanies it.” Benedict XVI, himself an accomplished musician, noted the “profound original bond” between Russian music and liturgical singing. “In the liturgy and from the liturgy is unleashed and to a great extent is initiated the artistic creativity of Russian musicians to create masterpieces that merit being better known in the Western world,” added the Pontiff. Drawing a deeper meaning from the concert, the Bishop of Rome affirmed that in music there is already a certain fulfillment of the “encounter, the dialogue, the synergy between East and West, as well as between tradition and modernity.” In his new book of interviews the Pope of Rome speaks very warmly of the performance.

Conclusion

I have said much today about classical and sacred music, as I compose and listen to it. Certainly, I am well aware of the insignificant number of young people who listen to classical music, whereas almost everyone listens to popular music. This I consider to be a real tragedy.

I believe, however, that secular musical art is possible within Christianity, including that which exceeds the limits of classical music which I love so much. Christianity is inclusive; it does not set strict canonical limits to art. Christianity can even inspire a secular artist who, using the means available and known to him and his milieu, will be able to convey certain sacred messages equally in the language of modern musical culture.

This applies also to modern, popular and youth music. There are compositions in popular music imbued with high spiritual content and are written skillfully (for instance, the famous rock opera Jesus Christ Superstar). No doubt, this composition is not in keeping with church criteria, but the author did not purport to present the canonical image of Christ. He achieved his objective outstandingly well by telling the story of Christ’s Passion in a language understandable to the youth and through the medium of contemporary music. I appreciate this music more emphatically than I do the works of many avant-garde composers, since the latter sometimes eschew melody, harmony, and inner content.

Some believe that there cannot be works of art dedicated to Christ except those created within the Church. I do not completely agree with this. Of course, the Church is the custodian of Christ’s teaching and the place of His living presence, but the Church should not seek to “privatize” Christ or declare Him to be her “property.” We should not repeat the mistakes of the Catholic Church made in the Middle Ages. The image of Christ can inspire not only church people, but also those who are still far from her. One should not forbid them to think, speak and write about Christ, unless they are moved by a desire deliberately to distort Christianity and to insult the Church and the faithful.

If a composition is bright, impressive and grips the listeners, if it makes them empathize emotionally with the Gospel events and even weep, if it arouses profound feelings in them, then it deserves high praise. It may be that we meet professionalism and musical skill in works which do not touch our hearts. It may also happen that a composition based on a religious subject turns out to be secular in its content and lacks spirit.

The way to the Christian faith often begins with a discovery of the living Christ, rather than a recognition of the church’s dogmatic truths. Christianity is a religion focused on the living Man, a historic person. The person of this Man appeals astonishingly. It may well be the case that a composition on a Gospel subject, though written by a non-Churchman, is imbued by a veneration of Christ. Many may begin their way to Christ and to the Church through such a composition, even if it were not altogether “canonical”.

Source: Real Clear Religion | Rod Dreher

Source: Real Clear Religion | Rod Dreher