Deprecated: trim(): Passing null to parameter #1 ($string) of type string is deprecated in

/home/aoiusa/public_html/wp-content/plugins/sexybookmarks/public.php on line

388

Deprecated: trim(): Passing null to parameter #1 ($string) of type string is deprecated in

/home/aoiusa/public_html/wp-content/plugins/sexybookmarks/public.php on line

394

Deprecated: trim(): Passing null to parameter #1 ($string) of type string is deprecated in

/home/aoiusa/public_html/wp-content/plugins/sexybookmarks/public.php on line

400

Readers will remember that Met. Elpidophoros gave the controversial speech at Holy Cross a few years back extolling the virtues of Constantinople and castigating America for ignoring it (see: Ecumenical Patriarchate: American ‘Diaspora’ must submit to Mother Church). It didn’t go over well at all. The next year he was invited to St. Vladimir’s Seminary and while not clarifying his remarks he ameliorated his tone (read .pdf).

Readers will remember that Met. Elpidophoros gave the controversial speech at Holy Cross a few years back extolling the virtues of Constantinople and castigating America for ignoring it (see: Ecumenical Patriarchate: American ‘Diaspora’ must submit to Mother Church). It didn’t go over well at all. The next year he was invited to St. Vladimir’s Seminary and while not clarifying his remarks he ameliorated his tone (read .pdf).

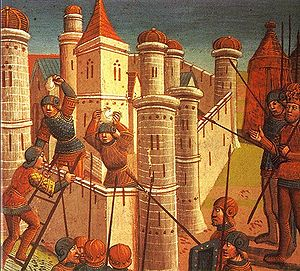

The homily contains much Byzantineze, some of it necessary because the social context of old world Orthodoxy demands it. What strikes our ears as excessive deference to the high authority, the Patriarch in this case, functions to show the courtiers gathered at the event that +Elpidophoros is a loyalist and will continue the Phanariot policies. Remember this is medieval practice carried forward. Also, the fact that Met. Hilarion was in attendance shows this was not run of the mill ordination.

Still, you can’t help but sense that the grandeur the language hopes to convey is laced with a sense of something already lost. I’m not sure that’s an entirely fair assessment and it is not meant to be unkind. Take the recounting of the history of Proussa for example. It’s tragic. Still, you wonder what is the meaning behind it all? Is the hope that one day Byzantine will be restored? Do the titular hiearchs represent the diaspora of those exiled from these ancient cities that one day will be organized as such, even in the diaspora? Has Byzantium become spiritualized; a kind of living abstraction held in abeyance in the confines of the Phanar yet at the same time the blueprint of that future hope? Take the last two paragraphs for example:

Finally, as the humble shepherd of an Eparchy of the Throne in Bithynia that presently lies in ruins, allow me convey a fervent greeting and modest hierarchical prayer and blessing to all those in the world that are from Proussa, Triglia and Moudania. And by way of conclusion, let me cite some hopeful lines from the poet George Seferis, composed on the occasion of his sojourn in Proussa:

By striking the salinity night and day

none has changed his fate;

By striking the darkness and light

none has changed the crime-scene.

Yet the light can reappear;

there on the heavy palms

the fruit can fall again.

And the blood can blossom once more.

Source: Hellenic News of America

HOMILY

Metropolitan Elpidophoros of Proussa During his Ordination to the Episcopate (Istanbul, March 20, 2011)

Your All-Holiness,

Your Beatitude,

Your Eminences and Graces,

Representatives of the Orthodox Churches,

Most Reverend choir of Hierarchs,

Your Excellencies Ministers,

Your Excellencies Ambassadors,

Honorable members of the Diplomatic Corps,

Honorable Rector of the University of Thessalonika,

Honorable Dean of the Theological School of Thessaloniki,

Honorable Mayors, Congressmen, Professors,

Beloved fathers, ladies and gentlemen,

By the ineffable divine economy and mercy, through the gracious recommendation of Your All-Holiness, and with the vote and approval of the Holy and Sacred Synod, which I have served over the years, I was unanimously elected Metropolitan of Proussa and today receive the third order of priesthood by the laying on of hands of my venerable Master and President of the First-Throne of Orthodoxy, with the concelebration of an apostolic number of revered hierarchs.

Bewildered and awe-struck, I was at a loss for thoughts and sentiments regarding the entirely sudden and extremely prestigious providence of God on my insignificance through Your All-Holiness, and recalled the customary expression of the memorable phanariot hierarchs, that the Phanar – the Patriarchal Court in general and the Synodal Secretariat in particular – constitute an Academy, a School, a University, wherein the younger clergy of the Mother Church as the future officers of the Ecumenical Patriarchate are formed and instructed, especially since the institutional and natural place for this, the Holy Theological School of Halki, unfortunately still remains closed.

The departure of a clergyman from the Patriarchal Court as a result of elevation is accordingly equivalent to a “graduation” from this School with a passing and perhaps even excellent grade. Therefore, I stand before you, Your All-Holiness, as a “graduate” in order to submit to the final test and give account for that which I have learned and with which I have been entrusted. (2 Tim. 3.14)

Nevertheless, since at this Patriarchal Academy there is only one chancellor and teacher and professor inasmuch as there is only one father and head and abbot, all teaching derives from him and all learning has him as a point of reference for all the fledglings of the phanariot education. Namely, the Patriarch! Our spiritual father, leader and instructor. His teaching adheres to the most efficient paedagogical method: personal example. Learning at the feet of the Patriarch signifies observation of his daily sacrificial service, personal experience of his anguish for the concern of all Churches, and cyrenaean sharing in the bearing of his unceasing burden.

Knowing from whom I have been taught (2 Tim. 3.14), I dare to list all that I have learned from him during the years of my tenure in the Patriarchal Court, beginning with the fundamentals such as the conduct of a younger clergyman, since a clergyman must not only be a good Christian and faithful member of the Church. He should also be adorned with the so-called natural virtues, including honoring one’s parents, teachers and every elder in stature and age; they also include diligence and industriousness, gratitude to all his benefactors, courtesy and affability, and generally a hospitable attitude to every visitor and pilgrim.

Our teacher at the Patriarchate is distinguished for the respect and honor which he reserves for those who have passed away, whether they be his predecessors on the Throne, hierarchs, clergy, parents, teachers, friends, and even janitors that faithfully served him. Wherever he may go, just as he returns with gifts for the living, he never fails to pray for the departed, sometimes also seeking to repatriate the sacred relics and precious remains of his holy predecessors, Patriarchs who died in exile.

Himself a lover of liturgy and of monasticism, he respectfully upholds the typikon and patriarchal order, simultaneously reminding us that the essence assumes priority over the detail, since “the Sabbath was made for man, and not man for the Sabbath.” (Mark 2.27)

My wise teacher taught me to love the Greek language, reading, studies and languages, encouraging us to learn constantly, to receive higher education, at the same time securing scholarships and other resources for travel to centers of learning in the east and west, all the while despite the fact that this implied deprivation for him of necessary clergy for the administration of the Phanar.

As a good shepherd and Bishop of the Most Holy Archdiocese of Constantinople, he knows his rational flock by name, always meeting with leaders of the community and hierarchs of the City for their needs, for the promotion of education, for the smooth operation of parish administration, for the securing and demand of property entrusted to us by our fathers and national benefactors. He provides for the renewal and adornment not only of the Patriarchal Offices and Patriarchal Church, but also for almost every holy Church, sacred Site, and precious Treasure of our Nation found within the jurisdiction of the Archdiocese and the other Metropolitan regions of our land.

As Patriarch, he is concerned with securing persons and staffing positions with individuals capable of responding to the contemporary demands not only of the Sacred Center but also of the Eparchies of the Throne throughout the world, establishing new missions and metropolitan dioceses, while installing select hierarchs for them and not depriving the overseas Institutions of the same attention.

As the First Hierarch of Orthodoxy, Your All-Holiness, you are a model of reverence for the synodal system, which you sought to promote and strengthen not only at the Phanar – initially by convening a regular Synaxis of the Hierarchs of the Throne and ultimately by reinstituting the invitation by rotation of all the active Metropolitans and Archbishops, regardless of citizenship, to the Holy and Sacred Synod – but also on a panorthodox level by introducing and establishing the institution of the Synaxis of the Primates of the Orthodox Churches, which proved most beneficial in responding to matters of panorthodox nature. This boldness of the First Hierarch through these initiatives was rewarded by the granting of Turkish citizenship as well to a number of hierarchs of the Throne. Inside the Synodal Hall of the Phanar, I personally and tangibly experienced the sacred work of synodal consultation in the Holy Spirit.

“Him who comes to me, I will not cast out” (John 6.37) is what my teacher is accustomed to saying, suffering for the division of Christians and not only promoting the official theological dialogues but also cultivating personal relations with leaders and officers of all rank among the non-Orthodox confessions and churches. The same teacher and father of our Nation grieves for the provision of peaceful coexistence and fraternal relations among the faithful of all religions, especially among Judaism, Christianity and Islam.

Your All-Holiness,

In full knowledge that I am encroaching upon the modest humility of my venerable Master, permit me to continue a while longer, boasting about my teacher even as I am yet possessed of the violent breathing of the Holy Spirit.

The summit of every thought and concern dominated by the Patriarch’s mind is the Ecumenical Throne, the much-afflicted Phanar, the Great Church of Christ, the Church of Christ’s Poor. His existence, his every intention and effort have as their ultimate aim the benefit of our Patriarchate. Each decision on any dilemma or challenge has as its foremost and exclusive criterion whatever is beneficial for the Mother Church. Above and beyond all lies the good of the Phanar, the projection of the ecumenicity of the Throne. This extremely powerful sense of obligation and duty toward the Ecumenical Throne on the part of my Patriarch, which reaches the point of overlooking his personal health and physical exhaustion, comprises for my insignificant person one of the most invaluable deposits, which I am taking with me from my time in the Patriarchal Court.

These and many others were the lessons that I learned, Your All-Holiness, at the great Academy of the Patriarchal Court. I made every effort to learn and assimilate as much as I possibly could, and I look to your lenient and paternal tolerance for wherever I failed, pledging that, even now outside the Patriarchal Court – although I shall always be within the saving and sacred grounds of the Phanar – I shall continue to serve my Patriarch and the holy Apostolic and Ecumenical Throne of Constantinople with all my strength and with the same spirit of learning.

Despite my shortcomings, I was elevated to Metropolitan of the vacant Eparchy of Proussa, one of the historical satellite cities of Constantinople on the Asian antipodes of Adrianoupolis. The city of Proussa, erected on the foothills of the snow-capped Mt. Olympus of Bithynia, constitutes a sacred city both for Orthodox Christians (inasmuch as it is replete with holy hermitages and monasteries on Olympus) and for Muslim believers (inasmuch as it contains the tombs of the founders of the Ottoman empire, Sultans Osman and Orhan). Many of my predecessor Bishops of Proussa adorn the Church Triumphant as Saints – whether Hieromartyrs, Righteous Ascetics, or god-bearing Fathers of Ecumenical Councils. I invoke the intercessions before the Lord of Saints Alexander, Patricius, George, Timothy and Theoktistos – all of them Bishops of Proussa – as well as of those martyred in Proussa: Acacius, Menander and Polyaenus, both for me and for all the children of the Metropolis of Proussa scattered throughout the world.

The Orthodox Christian population of the city, which thrived spiritually, ecclesiastically and materially, created particular impression on St. Gregory Palamas, whom we celebrate today, while the national benefactors Zarifi and Eustathios Eugenides competed for the establishment and preservation of schools in the region. For reasons known only to the Lord, Proussa, its seaport Moudania, Triglia, Syge and Elegmoi, the principal districts of the ecclesiastical jurisdiction of Proussa, were forcefully vacated, while those who survived settled in Greece, where they were recreated from the ashes by the grace and support of the holy, miraculous icon of the Virgin Mary of the Visitation. In venerating this renowned icon of the Mother of God and imploring her assistance for my journey henceforth, I bow down before the souls of all those who piously served as hierarchs in Proussa as well as of all the children who, as a result of the wretched turns of history, were painfully uprooted from their birthplace in the Metropolis assigned to me.

And now, Your All-Holiness, in assuming the responsibility of this eminent Eparchy of the Throne, with praises to the Lord who granted me such great mercy, I direct my mind, thought and eyes to you as my Father and Master, to whom – after God – I owe everything, in order that with profound emotion and contrite heart I may express my many filial thanks and gratefully venerate your precious right hand.

Thereafter, I would like to thank His Beatitude Archbishop Ieronymos of Athens and All-Greece, who greatly honored my modesty by undertaking such an exceptional journey abroad in order that, by his high presence and paternal prayer, and together with his honorable entourage, he might strengthen me as I begin the sacred ministry that lies before me.

Then, I respectfully turn toward the members of the Holy and Sacred Synod, who have honored me with their unanimous vote, gratefully bowing before them for the kindness and compassion which they demonstrated to my humble person. Moreover, I also thank all the holy Hierarchs who served as members of the Holy and Sacred Synod throughout my tenure as Chief Secretary for their affection toward me, for their sound counsel and for their cherished support in my responsible task.

Finally, I am thankful to many for the honor of their presence:

The Representative and other members of the honorable Greek Government

The Representative of the Opposition Party

The honorable diplomatic authorities

The representatives of the Churches of Alexandria, Antioch, Jerusalem, Russia, Serbia, Romania, Georgia and Cyprus

The venerable Hierarchs, who came and concelebrated or prayed with us< The Office of the Chancellor at the University of Thessalonika

The Representative of the Roman Catholic Church

The Representative of the Syro-Jacobite Church

The Representative of the Armenian Church

The Patriarchal Court in its entirety, headed by His Eminence Metropolitan Stephanos of Kallioupolis and Madyton

The representatives of the Holy Monasteries on Mt. Athos: Great Lavra, Vatopedi, Dionysiou, Pantokratoros, Agiou Pavlou, Xenofontos and Gregoriou,

My beloved parents Vasileios and Nadya

My brothers Edward, Paul and Xenophon, together with their families

My relatives, refugees from Eastern Thrace and Antioch

My colleagues, Professors at the Theological School of Thessalonika, together with my students

Those representing people from all over the world, who have their origins in Proussa, Triglia and Moudania

All the clergy, dear friends, distinguished colleagues at the Patriarchal Offices, teachers, community leaders and every citizen of this City.

Your All-Holiness, upon “graduating” from the School of the Phanar, in closing these words of gratitude, I wish to express my wholehearted prayer that we shall soon be deemed worthy of consecrating new and promising theological graduates of the Church at the Holy Theological School of Halki, whose reopening we hope for and anticipate as the culmination of your tireless efforts.

Finally, as the humble shepherd of an Eparchy of the Throne in Bithynia that presently lies in ruins, allow me convey a fervent greeting and modest hierarchical prayer and blessing to all those in the world that are from Proussa, Triglia and Moudania. And by way of conclusion, let me cite some hopeful lines from the poet George Seferis, composed on the occasion of his sojourn in Proussa:

By striking the salinity night and day

none has changed his fate;

By striking the darkness and light

none has changed the crime-scene.

Yet the light can reappear;

there on the heavy palms

the fruit can fall again.

And the blood can blossom once more.