Deprecated: trim(): Passing null to parameter #1 ($string) of type string is deprecated in

/home/aoiusa/public_html/wp-content/plugins/sexybookmarks/public.php on line

388

Deprecated: trim(): Passing null to parameter #1 ($string) of type string is deprecated in

/home/aoiusa/public_html/wp-content/plugins/sexybookmarks/public.php on line

394

Deprecated: trim(): Passing null to parameter #1 ($string) of type string is deprecated in

/home/aoiusa/public_html/wp-content/plugins/sexybookmarks/public.php on line

400

By John G. Panagiotou

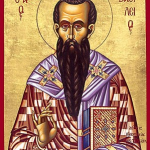

Many things are said and written about the great Cappodocian Father of the 4th century St. Basil the Great of Caesarea. In Basil the Great, we find the consummate theologian, liturgical scholar, ascetic and evangelist of the Faith. Too often, however, one more aspect of Basil is left overlooked and that is Basil as the first great Christian philanthropist. It is with this focus on Basil’s care, concern and heart for the poor, the underpriviledged, the sick, the unemployed, the homeless and disenfranchised that marks the level of profound theological reflection and insight that Basil exudes in his writings.

Many things are said and written about the great Cappodocian Father of the 4th century St. Basil the Great of Caesarea. In Basil the Great, we find the consummate theologian, liturgical scholar, ascetic and evangelist of the Faith. Too often, however, one more aspect of Basil is left overlooked and that is Basil as the first great Christian philanthropist. It is with this focus on Basil’s care, concern and heart for the poor, the underpriviledged, the sick, the unemployed, the homeless and disenfranchised that marks the level of profound theological reflection and insight that Basil exudes in his writings.

St. Basil the Great’s Early Life

Let us first, however, examine the context of the world in which Basil was born and matured in the Christian Faith so that we may better understand his notion of philanthropy. Basil was born into a wealthy established noble Greek Christian family in the city of Pontus in Asia Minor (modern day Turkey) in the year 330 A.D. By this time, nearly two decades had passed since the Emperor Constantine’s Edict of Milan which legalized Christianity in the Roman Empire. It was not long after this that Christianity would become the official religion of the Roman Empire.

Basil’s maternal grandfather was martyred for his unwillingness to deny the Faith in the years prior to the legalization of Christianity. Macrina his widowed maternal grandmother and his pious parents raised Basil and his four siblings in the Christian Faith. In all there were nine members in his family who would become recognized saints, especially of note was his sister Macrina (who was named after their maternal grandmother).

Basil would go on to study in the great prominent intellectual centers of the day such as Athens and Alexandria. During which time meeting and cultivating life-long friendships with luminaries such as St. Gregory of Nazianzus. He would finally complete his studies and open a law practice and tutorial service in rhetoric in the city of Caesarea. His life would radically change direction upon his meeting with the pious and charismatic bishop Evstathios of Sevasteia. After which, Basil would write that as a result of meeting with Evstathios, “I beheld the wonderful light of the Gospel truth and I recognized the nothingness of the wisdom of the princes of this world.”1

Basil would then be baptized at age 27. It is important to note that although infant baptism was practiced from the earliest days of the Church, delayed adult baptism of Christians was not uncommon during the first four centuries. We find both practices from Apostolic times.

The Monastic Tonsure and Preparation for Debate

Basil then headed to the Cappodocian region of Asia Minor (Turkey) to live for a time in the caves there. Prior to his Cappodocian departure, Basil would give his material goods to the poor, thus marking his monastic embarking with great Christian philanthropy. Upon his return from Cappodocia, he founded a monastic community on his family’s estate. It was within the monastic context that as part of the cenobetic rule of life in community that Basil would expose that is was with the understanding that it was to be a life of service to both those within the monastic community and to those outside of its walls. For Basil, asceticism in of itself could be self-serving and demonic if it were not tempered by service to others. Thus, his contribution to monastic endeavor was not limited to the ordering of a community, but in that community’s outreach and service to the greater community as a sense of mission and purpose. In his theological works, Moralia and Asketika, he outlines the guidelines for proper Christian living in the secular world2 and within the monastery walls.3

During this time, Basil would begin his great engagement of and in the tumultuous theological debates and controversies of the time. Namely, his contributions and renown would be made at the Council of Constantinople in his affirmation of the term” homoousios” (“the same essence”) in reference to Christ against the Arian heresy. It was his defense and articulation of the orthodox Christian teachings on the Holy Trinity, Christology and Incarnation that helped shaped the one holy catholic and apostolic Church’s theological formulations on these crucial matters of faith in the fourth century. Of all of his copious theological works which are too numerous to mention here, his On the Holy Spirit stands out as his appeal to Scripture and Tradition as the illuminators to the facts of the divinity and consubstantiality of the Holy Spirit with the Father and the Son.4 Thus, providing the formulation of three distinct “hypothesis” (Persons) in on Divine “ousia” (essence).

Of the hundreds of homilies, there exists the Lenten series entitled Hexaemeros which provide valuable parabolic moral teachings. These would articulate the moral chassis which would form the underpinnings of his Christian philanthropic worldview.

Philanthropy Emerges From Worship, Prayer, and Ascetic Practice

As with Basil’s delving into the monastic life, his approach to high academic theology does not remain merely in the theoretical. He makes it relevant precisely because he makes it applicable to the lives of the common members of society. Thus, in doing so, he makes it a ministry which reflects the Incarnation of Jesus Christ coming in the flesh and of life in communion with the Holy Trinity. This can be seen in his homily Sermon to the Rich where he instructs the hearer to treat the needs of other as we would treat our own, regardless of what those needs are.5

In the realm of liturgical theology, Basil is attributed with many prayers within the Eastern and Western rites. Most notably however are two that stand out above the rest and they come down to us through the Byzantine liturgical tradition: the Divine Liturgy of St. Basil the Great and the “Kneeling Prayers” at Pentecost Vespers. To what extent, these are the exact words penned by Basil verbatim is not the question that is important, the fact that they are attributed to him is reflective of his enduring influence and legacy of his focus on the synthesis of good liturgy through the formalization of liturgical prayers and hymnography with a sound theological basis. Throughout all of these works, Basil’s deep concern for the sick, the suffering, the hurting, the poor, the disadvantaged, and the oppressed is present throughout. Inn the anaphora (Eucharistic prayer) attributed to him in the Liturgy, the celebrant prayers, “defend the widows; protect the orphans; liberate the captives; heal the sick…For You, Lord, are the helper of the helpless, the hope of the hopeless, the Savior of the afflicted, the haven of the voyager, and the physician of the sick. Be all things to all, You know each person, his requests, his household, and his need.”6

Basil’s ascetical, theological and liturgical contributions alone would have assured him a place in church history. Yet, he would also, albeit reluctantly, contribute in the later years of his life to church history as a clergyman. In 362, Bishop Meletius of Antioch ordained him a deacon and he remained as such for three years until his ordination as a priest by Eusebios of Caesarea. It was during this time that the Arian controversy would rage and Basil would be very much involved.

Following the defeat of the Arians, Basil was appointed by Eusebios to become his assis him at the diocese and become his protosynkellos (chancellor). Basil quickly gained reputation and influence as a capable administrator. This became problematic because Eusebios became jealous and felt threatened by Basil so Eusebios permitted Basil to return to his asceticism, thereby leaving diocesan administrative life However, Gregory of Nazianzus persuaded Basil to return to diocesan service and there Basil remained for several years coexisting with Eusebios by giving him all the credit and acclaim for successes in the diocese.

Election to the Episcopacy

Upon the death of Eusebios in 370, Basil was elected bishop amidst opposition from others and his own apprehension and lack of desire to be elevated to the episcopacy. In St. John Chrysostom’s On the Priesthood, Chrysostom relates his coercion of Basil to accept ordination to the episcopacy for the good of the Church.7 In spite of all that, Basil would go on to have a dynamic and fruitful episcopacy. He came to see being a bishop not only as a burden which he definitely felt it was for him, but as an opportunity to even greater service because of his episcopal office.

With this in mind, Basil established the first formal soup kitchen, hospital, homeless shelter, hospice, poorhouse, orphanage, reform center for thieves, women’s center for those leaving prostitution and many other ministries. All the while, Basil was personally involved and invested in the projects and process. He gave all of his personal wealth to fund the ministry to the poor and downtrodden of society. All of these ministries were given freely to all who sought help regardless of their religious affiliation. Basil himself would put on an apron and work in the soup kitchen. He would refuse to make any discrimination when it came to people who needed help saying that “the digestive systems of the Jew and the Christian are indistinguishable”.88

In addition to all of the above, Basil would maintain a daily schedule of morning and evening schedule of liturgy and preaching at his own church. He saw that the outreach ministry, as importantly vital as it is, is to be seen within the context of worship and prayer.

Finally, Basil had built a large ministry complex outside of the city walls which included a poorhouse, hospital and hospice. It was called the Basiliad. For a variety of reasons, one being its consolidation of outreach ministries into one centralized location outside of the confines of city walls gained it great world fame because like many other things, Basil was the first to conceive of and realize something as ambitious such as this.

Basil died on January 1, 379 at the age of 49 suffering from liver disease. Customarily in Greece, St. Basil’s Day (January 1) was when gifts would be exchanged. Also, a sweet bread is baked for that day with a coin inside. Both of these customs emerged as an expression of the Christian philanthropy exemplified by Basil.

To Be in Christ is to Engage the World

It is interesting to note that Basil is sometimes referred to as “Ouranofantora” (“revealer of heavenly mysteries”). Perhaps, the greatest revelation that we can receive from Basil is that to truly be “in Christ” means necessarily having to engage the world and all of its problems, trials, and tribulations with radical trust that God will deliver us and provide for us. What are the implications for today’s Christian? What are the implications for the contemporary Church? In the last portion of my article, I want to explore these concepts and their implications offering what might be a viable blueprint for meaningful expression of Basil’s radical ancient Christian worldview in today’s context.

First, people are formed by people. What more could be said by the fact that Basil grew up and was nurtured in a spiritual household that was even marked by the family patriarch being martyred during the persecution. Within that context, the piety of his grandmother and parents shaped the man who he became. There is no substitute for authentic piety. The charity and love that begins at home cannot help but expand beyond the house door. It is a truism in life that the people we have around us define our identity today and mold our identity tomorrow. For the Christian, we should seek out pious people.

Second, people are moved to action by people. When Basil meets with Evstathios of Sevasteia, it is Evstathios’ charisma and radiance that inspires Basil to embark on a new life journey. It was not lofty theological treatises or ornamental grandeur that impresses him. Rather, it is Evstathios’ personhood. It is precisely this personal focus which focuses ontologically who are a person is not functional definition which focuses on what function a person performs. The “Evstathios” in our lives can take many forms. He may be a plumber who inspires us to live fully for God by whom he is Christ, not what station in life one holds. God always works in the personal often speaking to us through others if we are open to him.

Third, Basil whether in ascetical reflection, theological debate, or in the midst of chancery politics, let God use Him for His greater glory unto service of others. He did not make an excuse for not being a philanthropist in the hermitic caves of Cappodocia by saying what can I do here for others in this remote isolation. He did not make an excuse for not being a philanthropist by his attendance and involvement in the Ecumenical Council and other synods defending the Faith. And he did not make an excuse for not being a philanthropist while he worked in the political world of the diocese and hierarchy. Instead, he used his stations and positions in life to promote the Gospel and minister unto people who were in need.

Instead of Liberation Theology or the Social Gospel is Basil’s Church as Hospital

Make no mistake, Basil was not an ancient versions of a promulgator of “Liberation Theology”. To think that is to utterly miss the point of the man, his message, and his ministry. He never saw his role of addressing an injustice and relating it back to Christ and working for social change in humanistic political terms. Rather, he saw his role as abiding Christ and seeing a world through His Divine ocular lenses in hopes of leading and helping everyone come unto Him for transformation and transfiguration. Rather, Basil is consonant with his view of the Church with the likes of his contemporary St. John Chrysostom who reckons the Church as the spiritual hospital. Basil, as with so much of his theology, takes this theoretical premise and literally makes it incarnational.

In the Body of Christ today, we hear rhetoric such as “we can only do so much” or “we can only help ‘our own’”. That mentality is totally antithetical to the teachings and “fronima” (mindset) of Basil the Great. To really understand and grasp, the essential iconic image of Basil, we should not just be see him in Byzantine episcopal vestments, but rather in wearing an apron in a soup kitchen serving and identifying with the poor, the homeless and the disenfranchised.

We as individual believers and collectively as the Church are called to Christian philanthropy. It is ancient. In view of the Lord Jesus’ words in Matthew 25, it is essential not optional. Anything short of this and we are failing our calling as shown to us by Basil the Great. Yes, it is the mission of the Church to minister to the poor, homeless, unemployed and disadvantaged. Ministries to those in need should be held daily, not just occasionally. It should be just as regular in schedule as any other liturgy, Bible study, or meeting at the Church.

For far too long, the Church has lived under the fallacy that it is not supposed to prosyletize, only to use that as an excuse for it not to evangelize, thus failing in the Great Commission through the sin of omission. Now, more than ever with the world as it is, to miss the opportunity to serve because of the fallacy that “the Church is not a social service center”, only to use that as an excuse not to serve and help those in need whatever the multitude of needs may be is to fail in the mission of the Church, as St. Basil believed it to be and taught it should be through his example. For if we ascribe merely to a nominal definition of what Church is as merely being in unity of doctrinal faith with St. Basil and yet not incorporate the essential meanings and practice of his life, then we deceive ourselves because we are not authentical practicing Christianity. It is time for us to put our aprons on and get to work in that soup kitchen, in that hospice, in that nursing home, in that homeless shelter and anywhere else God leads you to serve and minister.

ENDNOTES

1 Basil the Great, Epistle 223, 2, as quoted in Patrology, v. 3. Christian Classics trans. Quasten, Johannes (1986) p. 205.

2 Basil the Great, Asketiki Prodiatiposis, Athn., De Syn. v. 31, in Christian Classics Ethereal Library, p. 467.

3 Basil the Great, Moralia, Nicene and Post-Nicene Fathers Series II, v. 8.

4 Basil the Great, On the Holy Spirit, St. Vladimir’s Seminary Press, (1980).

5 Basil the Great, Sermon to the Rich, [bekkos.wordpress.com/st-basils-sermon-to-the-rich/]

6 Divine Liturgy of St. Basil the Great, edited trans. Vaporis, Nomikos M., Holy Cross Orthodox Press, (1986).

7 John Chrysostom, On the Priesthood, St. Vladimir’s Seminary Press, (1996).

8 Kiefer, James E. Basil the Great, Bishop, Theologian [http;//justus.anglican.org/resources/bio/186.html]

9 John Chrysostom, “Homily Against Publishing the Errors of the Brethren”, Patrologia Graeca 62, trans. edited by Migne, Jacques. pp. 755-57; see also Vlahos, Ierotheos. Orthodox Psychotherapy, Birth of Theotokos Monastery publisher, (2005), pp. 25-26.

John G. Panagiotou is a graduate of St. Vladimir’s Orthodox Theological Seminary and Wheeling Jesuit University. He is the owner of Zeon Financial Group which provides insurance and retirement solutions. You may connect with him at johnpan777@gmail.com and on LinkedIn.

Source: Antiochian Orthodox Archdiocese

Source: Antiochian Orthodox Archdiocese