Deprecated: trim(): Passing null to parameter #1 ($string) of type string is deprecated in

/home/aoiusa/public_html/wp-content/plugins/sexybookmarks/public.php on line

388

Deprecated: trim(): Passing null to parameter #1 ($string) of type string is deprecated in

/home/aoiusa/public_html/wp-content/plugins/sexybookmarks/public.php on line

394

Deprecated: trim(): Passing null to parameter #1 ($string) of type string is deprecated in

/home/aoiusa/public_html/wp-content/plugins/sexybookmarks/public.php on line

400

Source: OrthodoxyToday.org | George C. Michalopulos

Christopher Hitchens, perhaps the most famous of the New Atheists, has spent the better part of the past year engaging in a series of well-publicized debates, inveighing with his typical eloquence against theism in all its forms. Most of his correspondents have been Christians. Men such as Dinesh D’Souza, Bill Dembski, Tony Blair, and even his brother, Peter have debated him in public forums. (Interestingly enough, another atheist, David Berlinski, has debated him as well, taking him to task for his inability to see the carnage that atheism inevitably leads to.)

Although Hitchens is suffering from esophageal cancer, he continues to speak with his customary eloquence and wit. Unfortunately, as of late much of his argumentation is devoid of rigorous logic. Instead he has taken an emotional tone, one based on resentment of the concept of a Deity and what He stands for rather than the cold and precise voice that is called for in justifying the alternate belief in materialism. His pronouncements are increasingly dogmatic and devoid of any of the skepticism that is expected to be found in rationalist precincts. It’s not too much to say that in these latter days of his life, he eschews the rationality of his beliefs and even relies on secular myths in order to buttress his faith in non-faith. The pose of the wounded lover is all-too-apparent. This is confusing, as he’s still very much the moralist who appears to believe in good and evil. Not seeming to understand that rationalism is morally neutral, he has the decided mien of a hellfire-and-brimstone preacher.

Christopher Hitchens

Hitchens’ rationales for anti-theism of late provide much fodder for criticism. My purpose at present is to concentrate on one aspect of his argumentation, specifically his present invective against the Old Testament. Although his hatred of Christianity is palpable, I have come to believe that there is another, more subtle, hatred at work as well. One that predates the institution of the Church and which arises out of paganism itself. What I am talking about is nothing less than a species of anti-Semitism. Is it possible as one critic has recently stated that Hitchens has a “Jewish problem,” one that “has been an open secret for years”?

i

Although distinctions have been drawn between anti-Semitism as a racialist phenomenon and anti-Judaism (certainly Hitchens relies upon them), in reality it is difficult if not impossible to divorce these two hatreds. It is my contention that Judaism and Semitism are two sides of the same coin. To postulate what I am saying in a positive fashion, I would state that for all practical purposes Semitism is the vehicle of monotheism throughout history and constitutes a proof of Providence-–evidence for God, so to speak. This was achieved because the Jews as a people were receptive to the very words of God Himself, and that they transmitted them to humanity. It was by this mechanism (revelation) that human civilization evolved from paganism and naturalism to monotheism and morality. As I shall strive to prove in what follows, it is my contention that Hitchens’ anti-theism cannot be divorced from his virulent anti-Judaism. Indeed, the latter invariably leads to the former.

The Old Testament: Fact or Fiction?

In the past, atheists have often denigrated Christianity as a Hellenized Judaism, a hybrid cult not unlike the ancient Greco-Oriental mystery religions. Examples would include the cults associated with Mithras, Orpheus, or Dionysius. This of course would mean that like these other demigods, Jesus was a mythical figure as well, with absolutely no historical foundation whatsoever. This was even the official view of Soviet historiographers for a time.ii

Unfortunately for the holders of this view, documentary evidence for the historicity of Jesus exists outside of the New Testament, ranging from the positive to the scurrilous. Most atheists therefore today concede that the evidence for His existence is too great to be denied and have chosen instead to denigrate the miraculous aspects of His life.

For Hitchens this isn’t good enough. In his recent books, God is Not Great: How Religion Poisons Everything, he makes the claim that all religion is evil, bar none. Not only is religion in all its forms evil, it cannot in his mind have any redeeming qualities whatsoever. Not content to merely revile Islam and Christianity, he goes to great lengths to castigate Judaism as well. Thus in his mind, the process by which the mohel circumcises an infant boy is accorded the same horror that is attendant when the jihadi straps on his suicide vest and blows up a pizzeria. This is clearly a perspective that lacks any proportion. It is as delusional as comparing the Boy Scouts to the Hitler Youth.

This is indeed ironic as Hitchens is part Jewish on his mother’s side. How then does he square this circle? Simple: in Hitchens’ mind, there is nothing at all special about being Jewish. Indeed, according to him, the Jews as a distinct people don’t exist. Like Christianity which in his mind is similarly a made-up religion, Hitchens posits that Judaism –both the people and the religion—arose gradually over the centuries. He believes that many of its foundational structures are pure fantasy. Somehow, individual people and tribes who happened to live in Canaan chose somehow to coalesce into a people that retroactively created an Abrahamic ancestor and all the accoutrements associated with him, including the sagas associated with his descendants, the Exodus from Egypt, and of course the Mosaic Covenant. To his credit, he won’t go so far as modern Islamic fantasists have gone and denied the existence of the Second Jewish Commonwealth or the origin of the Jews in Palestine itself, but one can’t help but wonder that he could wish them away if he could, seeing as how Israel has become a proxy for all that is evil about the West, including colonialism and imperialism.

Roman soldiers carrying the Golden Menorah as plunder.

One reason why he can’t venture into Islamist denialism is that the existence of the Second Jewish Commonwealth is well-attested in the historical record. Coins from the Hasmonean dynasty literally dot the landscape of modern Israel. The Arch of Titus famously depicts Roman soldiers carrying the golden menorah of the Temple as plunder. The writings of Flavius Josephus, Tacitus, and Suetonius, clearly attest to the existence of an independent Jewish kingdom which was alternately a dependency, colony, and protectorate of the Roman Empire. This is all undeniable.

The pre-Hasmonean kingdoms of Israel and Judah likewise boast impressive historical credentials. Things get dicey however when we get further back in the mists of time. Evidence outside the Bible for the history of Israel in the pre-monarchic period –the time of the Judges—is rather scant. And the further back one goes –to the Mosaic period in particular—then one must rely almost exclusively on the Old Testament itself, specifically the Pentateuch and later secular documents. These five books, which are ascribed to Moses contains significant anachronisms, most famously a description of the death of Moses, its putative author.

Therefore, the Exodus is a particular sticking point for Hitchens. In a recent debate with Bill Dembski, he labels the Exodus as a complete fantasy. For proof of this assertion, he cites Israeli archaeologists who were supposedly given a mandate by David Ben-Gurion, the founder of Israel, to search for evidence of it in the Sinai Peninsula once it had been captured from Egypt following the Six-Day War of June, 1967. According to Hitchens, they were completely unable to come up with any evidence for an ancient flight from Egypt whatsoever.iii Therefore, because these archaeologists were unable to do so, then we must believe that this ancient story is demolished because it failed the argument for interest.

Hitchens did not come to this conclusion on his own. In fact, it is the reigning orthodoxy of a wide band of archaeologists, some of who are Jews themselves. Names like Ze’ev Hertzog and Israel Finkelstein are accorded an almost papal-like infallibility when they dogmatize on the complete fictitiousness of the Exodus in all its particulars. One of the sacred texts (as it were) of this revisionism is The Bible Unearthed: Archaeology’s New Vision of Ancient Israel and the Origin of Its Sacred Texts.iv Its authors, Israel Finkelstein and Neil Asher Silberman, are clearly within the modernist/secularist view. According to these authors there is absolutely no trace of a mass migration in the Sinai Peninsula. For proof they categorically state that given that “modern archaeological techniques are quite capable of tracing even the meager remains of hunter-gatherers and pastoral nomads.”v The Sinai we are told contains no such evidence.

Hitchens takes such dogmatism literally and runs with it. Unfortunately, this puts him on a precarious limb, one which Finkelstein and Silberman shy away from in certain crucial respects (as shall be pointed out in due course). For one thing, he is ignorant of the controversies which range about in modern archaeological circles. Quite simply, one generation’s certitudes very often become the next generation’s laughingstocks. This is especially true in the field of Biblical archaeology. One has only to engage in the area of Dead Sea Scroll studies to realize that researchers looking at the exact same document can come to completely different conclusions.vi Even the nature of the community found in the Qumran caves is far from a settled matter. Be that as it may, the discipline of archaeology cannot be viewed with blinders. If all we had to go on were artifacts, then our understanding of history would be dim indeed. Usually it is documents and actual knowledge of historical events (or folkloric remembrances of the same) which guide the interpretation of archaeology. That is why Heinrich Schliemann could spend his vast wealth uncovering the ruins of Mycenae and Troy, not because he was a philhellene who had money to burn while on vacation but because he believed that the Homeric epics were not fictitious. In the main, he was largely correct.

The king-list in the temple of Sethos I at Abydos, showing Old Kingdom names

In regards to historicity of the Exodus, revisionists often find themselves on the horns of a dilemma. Unlike Hitchens, precious few of them disbelieve in the antiquity of the Israelite nation or its interaction with ancient Egypt. For one thing, the concept of a people called Israel and their wars with Egypt was known to the Egyptians, who gave it their own spin. Manetho, a Greco-Egyptian priest who flourished in the third century BC writes about the expulsion of the Hebrews in triumphant, nationalistic tones. Likewise, the Mernaptah Stele, which is dated to no later than 1210 BC, talks about punishing raids on the Israelites by Mernaptah, the son of Ramses II, the Great. Interestingly, the wording on the stele lists several nations destroyed by Merneptah, Israel among them. However, unlike the other nations mentioned, Israel is not considered a nation-state but a people. Although this designation accords quite well with what we know about the people of Israel in the time of the judges, it also shows that they were not in Egypt and certainly not slaves, but powerful enough (even as a loose confederation of tribes) to challenge the might of the Egyptian nation.

How then did the Israelites acquire the story of their Exodus from Egypt? And why did they view themselves as slaves in this saga instead of the powerful nation that they might have been (at least comparatively speaking)? Further, if the events depicted on Mernaptah’s stele not coincident with the Exodus, does it mean that the ancestors of the Israelites were never in Egypt or in subjugation to the Egyptians during a previous time?

As mentioned above, Manetho’s account largely agrees with the rough particulars of the Exodus with some important exceptions. For him, a group of savage Semites from the East burst into Egypt as interlopers, attained great station, and then subjugated the natives. During their time there, great famines and plagues were visited on the land. However, thanks to a rebellion led by a native subject-king, they were driven out and the Egyptian nation was restored. Tacitus, writing much later in his Histories, concentrates on the issue of the plagues and the subsequent expulsion. So too does the Ipuwer Papyrus. In fact, the story of Semites living in Egypt as isolated groups of wanderers seeking to water their herds, or as migrant laborers, mercenaries, or even statesmen is not controversial at all. Finkelstein and Silberman for one certainly don’t discount it. As they themselves state, the plenteous water of the Nile valley long made Egypt the destination of choice for the semi-nomadic Semites of Canaan who struggled with uneven rainfall in their native lands.

Bust of Antiochus IV at the Altes Museum in Berlin.

As mentioned, the most famous Semitic group which flourished in Egypt were the Hyksos, who were finally driven out of Egypt in a massive pogrom in 1570 BC. According to Manetho, the term

hyksos was a Greek word which meant “shepherd kings.” (Curiously this word is nowhere found in any ancient Greek lexicon.) Regardless, this story as recounted by Manetho is not unlike the picture that the Book of Genesis paints of Abraham and his descendants –pastoralists of great wealth who eventually came to vast power in Egypt, only to have their descendants leave in defeat some time later.

If however Finkelstein, Hertzog, and others are correct that there is absolutely no archaeological evidence whatsoever for an Exodus from Egypt, then how did this story arise? It is here that the revisionists ask us to believe something improbable. According to these revisionists, “the Bible may reflect a New Kingdom reality.”viii That is to say that the entire history of pre-monarchic Israel was manufactured out of whole cloth during the time of King Josiah of Judah in the seventh century in order to serve as a vehicle for his ambitious program of national renewal. As for the Exodus story itself, it was nothing more than military propaganda which was used by Josiah in his war against a resurgent Egypt, one needed in order to whip up Jewish anger against the Egyptians as a type of pre-war hysteria. In other words, Josiah and his propagandists somehow came to appropriate the history of the Hyksos as their own. Not only that, but they had to distort it completely; now the Hyksos/Hebrews were the oppressed rather than the oppressor during their sojourn in Egypt. Once that was complete, then Josiah and his minions brainwashed the Jewish people into accepting it without question. Leaving aside the improbability of such a happenstance, the implications do not stop there. In fact what follows is almost too fantastic to believe: armed with this new myth, the historically ignorant people of Judah willingly went to war against the most powerful nation on earth.

Finkelstein and Silberman however cannot bring themselves to accept the full implications of this theory, which begins and ends with the proposition that the Exodus is a complete fantasy. In walking back from the precipice, they try to have it both ways. For them,

…the saga of Israel’s Exodus from Egypt is neither historical truth nor literary fiction. It is a powerful expression of memory and hope in a world in the midst of change. The confrontation between Moses and pharaoh mirrored the momentous confrontation between the young King Josiah and the newly crowned Pharoah Necho. To pin this biblical image down to a single date is to betray the story’s deepest meaning. Passover continues to be not a single event but a continuing experience of national resistance against the powers that be.ix

Though poetic and indicative of a larger truth, this summation is unsatisfying –one could say little more than wishful thinking on the authors’ parts. Quite simply, it leaves unanswered many basic questions and relies on too many glib assertions. Given such presumptions, one should be reluctant to disregard the primary documents of the Exodus narrative simply because the archaeological evidence is (supposedly) so scant. Finkelstein seems to be aware that he is on the horns of a dilemma; he therefore gives himself some wiggle room. Rather than accept the Cecil B DeMille-like numbers of a massive migration of hundreds of thousands of people tramping across the desert for forty years, the authors concede that the expulsion from Egypt could have been a far smaller event and that the larger numbers of the traditional tale reflects instead the typical attribute of exaggeration to which later generations are prone. They go on to say that perhaps what is recounted in a grandiose fashion was not a singular, massive migration but a series of minor migrations that transpired over many generations. Regardless, somehow we are to suppose that during the period in question, the Israelites acquired a unique understanding of themselves and their national deity, which they later codified in the famous Mosaic covenant.

Jews cross Red Sea pursued by Pharoah. Fresco from Dura Europos synagogue

Be that as it may, this interpretation of the meaning of Passover is largely correct, at least in the theological sense. The Exodus is very much the story of a group of despised outcasts standing up in the face of brutal oppression and submitting themselves to a transcendent God who is more than a mere force of nature. He is in fact their very savior. In this respect, Finkelstein and Silberman choose to view it the way theologians throughout the centuries have done. They admit as well that the “main outlines of the story were certainly known long before the [the time of Josiah].” For proof of the traditional understanding of the Exodus, the authors point for example to the prophets Hosea and Amos, who told the story of the Exodus a full century

before the time of King Josiah and his alleged fantasists.

x Although by this admission, they display a generosity to tradition, this is still rather confusing.

To answer this dilemma, Finkelstein and Silberman state that they agree with other scholars who speculate that the turbulent story of the Hyksos and their violent expulsion from Egypt resonated with all the Semites of Canaan for centuries, so much so that it became “[the] central, shared memory of the people of Canaan.”xi This may be true but they offer no evidence that the many other Semitic nations viewed the expulsion of the Hyksos with horror or that they likewise appropriated it as their own historical myth (this assumes that the Israelites did so as well). What about the Assyrians, the Babylonians, or the Phoenicians? What writings have they produced which shows them to be the persecuted descendants of the Hyksos (or for that matter, the savage conquerors of the mighty Egyptians?) Be that as it may, why did the Israelites, alone among all Semitic nations, do so, or at least choose to appropriate the expulsion of the Hyksos (if not their earlier triumph) as their story? And how could they distort the actual facts so completely, particularly that the Hyksos were not the oppressors but the oppressed?

We can go even further. Quite simply, a generalized remembrance and/or appropriation of this atrocity—if true—cannot explain the origin of the Sinaitic covenant and the necessity which compelled the Israelites to view themselves as “a people apart.” Instead, Finkelstein and Silberman revert to talk of the Passover being a metaphor for an estranged people who stood up to violent oppression (which it certainly is to a very great extent) without giving any inkling into how it came about in the first place. The onus is upon the revisionists who believe that the Exodus story is a “complete fantasy.”

Unfortunately, the generous view of the Passover narrative as offered by these authors is not accepted by the New Atheists, who in their worship of all things reductionist, cannot accept the moral imperative of the Decalogue handed down to Moses by God. For them, the adherence to materialism is so absolute that nothing less than complete nihilism will do. As far as they are concerned, the paucity of evidence for the Exodus is all that matters. More disturbingly, Hitchens’ vaunted championship of all things anti-colonialist stops at the door of the Jews, who set the template of an oppressed people overthrowing colonialist overlords during the Maccabean revolt. For Hitchens, the steadfastness of the Jews in the face of the extermination of their culture (which he calls “tribal Jewish backwardness”) was nothing less than a crime against humanity. Thus, the crimes of Antiochus IV Epiphanes, an ancient monster (who was probably delusional) are wiped clean and this ancient king is exonerated because all he wanted to do was “[wean the Jewish people] away from the sacrifices, the circumcisions, the belief in a special relationship with God, and the other reactionary manifestations of an ancient and cruel faith.” (That modern Palestinian Arabs espouse essentially the same mindset if of no consequence to Hitchens, who goes out of his way to sympathize with the sentiments that give rise to their exterminationist rhetoric of all things Jewish.)xii

Is there a “Biological” Judaism?

To be sure, Hitchens is not the first person to throw cold water on the concept of the distinctiveness of the Jewish people. Certain Jewish and Israeli scholars such as Arthur Koestler, Frank Makow, Israel Shahak, and Schlomo Sand have long been barking up this tree with the same questionable results. As mentioned above, Finkelstein and Silberman have concocted a narrative of Israelite formation that was much more diverse, heterogeneous, gradual, and far later than what is commonly believed. They go on to say that the Torah is essentially nothing more than a myth, propagated in the seventh century by the Judean king Josiah to fashion a historical pedigree for his resurgent kingdom which was otherwise rather parvenu. In other words, the Israelite nation simply arose over many centuries, in which several different nations and tribes living in and around Palestine simply coalesced into a new nation. They somehow accepted the Hyksos story as their own and horribly distorted its particulars. In order to account for the origin of the Hyksos, they created a foundational myth using several insignificant figures –and not a few mythical ones—from the dim past as templates.

But why stop there? Why not take this revisionism to its logical conclusion? If there was no Exodus, no Decalogue, no theocracy under the Judges, and no Davidic kingdom, then why should we believe that the Jews are who they say they are? Hitchens of course cannot completely go down this road –he’s far too intelligent for that. However others have, and before the onset of DNA technology, a cottage industry arose which was able to throw considerable water on the idea of the concept of Jewish distinctiveness, at least for a considerable number of people of a curious disposition.

As such, not only are the tales of the Old Testament fantasy, but the uniqueness of the Jewish people themselves is as well. Before we can address these claims, a brief history is in order. Presently, the Jewish people, who are mainly the remnants of the Southern tribes of Judah and Benjamin (and the Levites who lived among them), can trace their ancestry back to the Roman dispersions that followed the First and Second Jewish Wars (AD 70 and 135, respectively). Depending on their point of final destination, they are denominated as Sephardim (those who migrated to Iberia/North Africa), Mizraichim (Egypt and the Levant), and Ashkenazim (Eastern European) Jews. An earlier group, the Romaniotes, settled in Greece some two centuries before the great diaspora of AD 70. Presently, the Ashkenazim constitute the overwhelming majority of modern Jewry, some 80 percent or greater according to some estimates.

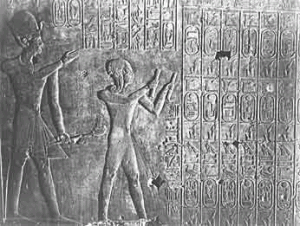

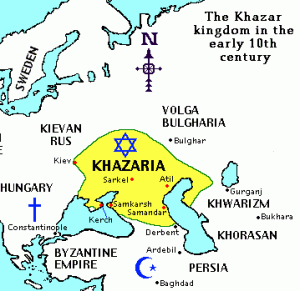

It is among the Ashkenazim that the greater part of the demythologizers and revisionists have concentrated their fire. For them, the Jews of Eastern Europe are not really descendants of the Jews of Palestine but an interloper race of Khazars, a Turko-Mongolian tribe that inhabited the Crimea during the Middle Ages. As such, they are not racially related to the Sephardic, Mizraichic, or Romaniote Jews. In other words, they are not even of Palestinian origin at all.

The Khazars are certainly an interesting case study. As an empire, they flourished ca AD 700-1000. The importance of their empire to Byzantium can be discerned by the protocols which the Byzantines attached to its khagans, whom they deemed second in rank to the Caliph of Baghdad among the non-Christian potentates of the world.xiii Intermarriage between the royal houses of Byzantium and the Khazars was practiced as well: Leo VI, the Wise, is often called Leo the Khazar because of his mother, who was a Khazar princess. Be that as it may, it was widely known that their khans converted to Judaism in order to keep a studied but respectful neutrality between the Orthodox Byzantines and the Baghdad Caliphate, both of whom brought exceeding pressure to convert them to their respective religions. It is assumed therefore that their boyar class likewise embraced Rabbinic Judaism. What is unknown is to what extent the rest of the population did so.

The Khazars are certainly an interesting case study. As an empire, they flourished ca AD 700-1000. The importance of their empire to Byzantium can be discerned by the protocols which the Byzantines attached to its khagans, whom they deemed second in rank to the Caliph of Baghdad among the non-Christian potentates of the world.xiii Intermarriage between the royal houses of Byzantium and the Khazars was practiced as well: Leo VI, the Wise, is often called Leo the Khazar because of his mother, who was a Khazar princess. Be that as it may, it was widely known that their khans converted to Judaism in order to keep a studied but respectful neutrality between the Orthodox Byzantines and the Baghdad Caliphate, both of whom brought exceeding pressure to convert them to their respective religions. It is assumed therefore that their boyar class likewise embraced Rabbinic Judaism. What is unknown is to what extent the rest of the population did so.

Some modern revisionists assume that the Khazars converted to Judaism en masse. Clearly the Byzantines were worried about such a scenario coming about. We know for example that St Cyril was sent to the royal court of the khagans in order to somehow steer them away from Judaism. As such, he undertook an intense study of Hebrew in order to debate with the rabbis who were then advising the Khazar nobility. Although his missionary effort failed, his knowledge of Hebrew came in handy during the later (and more successful) missionary effort in Moravia, when Cyril and his brother Methodius devised the so-called Cyrillic alphabet for the Slavonic language. (Although the Cyrillic alphabet is predominantly Greek, it contains at least five letters which are clearly Hebrew in origin.)

The most famous proponent of the Khazar mass-conversion into Eastern European Jewry was the late Arthur Koestler (who was himself Jewish). In his last work, The Thirteenth Tribe, he lays out an impressive case for this alleged event. Since then, other historiographers and revisionists have taken up the cause of the Khazars as the progenitors of the Jewish people. Unlike Koestler however, many who do so are of an unsavory nature and use this myth to buttress their antipathy to the Jews as a whole. In their febrile imaginings, the necessity of the Khazar origin for the Ashkenazim wipes away the taint of anti-Semitism because the modern Jews are not really Semites at all but a Turkic people who somehow finagled their way into the stock of Abraham, not unlike the ancient inhabitants of Palestine who we are told by other revisionists somehow created the Abrahamic foundation of Israel for reasons that we cannot ascertain. Hence the necessity for the state of Israel as a safe haven for the Jews is negated by this ploy.

Unfortunately for the revisionists, the belief that the Jews are an agglomeration of other peoples that somehow chose to merge into an insignificant (and persecuted) tribe with a curious and unnatural religion is no longer tenable. Thanks to modern DNA technology, we now know that the common descent of Jews all over the world is an established fact.xiv This is not to say that the Jews are a “pure” race or that they don’t carry the genes of other nations, but that the high incidence of common genes found in isolated Jewish groups the world over proves to a reliable degree that their foundational “myth” is largely true.

At this point a further digression is in order. One of the strongest evidences for Jewish antiquity is found in the priestly caste of cohanim. Males who bear the name Cohen, Kagan, Kahn, etc., bear a common genetic mutation on the Y chromosome (which is only passed from father to son). This mutation is found in Jews throughout the world, even among populations which vary widely in physiognomy such as the Lemba of southern Africa who have predominantly negroid features. The frequency of mutation in this gene indicates a chronology which pinpoints the common ancestor of this caste who flourished in Canaan over three thousand years ago, roughly the time in which Aaron, the first high priest of Israel is traditionally believed to have lived. Therefore traditional Jewish impetus for endogamy is borne out by the genetic evidence –often not in their favor, given the high incidence of genetic diseases which Ashkenazic Jews are prone to.

Often, the study of DNA leads to some interesting (and unsettling) detours. For example, there is a high incidence of Jewish ancestry among a significant minority of Palestinian Arabs, especially among those families which have maintained a long, multi-generational existence in Palestine (as opposed to the majority who are descendants of migrants from other lands). Likewise, many of the Arab royal houses have some Jewish ancestry. This should be expected since most Arabic nobility is descended from Mohammed, who according to a well-established tradition, was married to at least one Jewess.xv

Of course, there are significant hiccups in this tale of racial homogeneity. It is clear that the various physiognomies that exist among Jews throughout the world tell a tale of intermarriage with host populations. This is obvious. But much of this phenomenon can also be explained by genetic drift as well as by intermarriage (and rape). Genetic drift results when certain genetic traits become intensified due to isolation from a host population. These traits are usually part of a “founder effect,” which are augmented over time in endogamous populations. (The founder effect of the Ashkanazim indicates an original population of predominantly Jewish males from Palestine and a significant percentage of native European wives. The Sephardim and Mizrahim on the other hand were founded mainly by Jews who migrated as families from Palestine.) In any event, genetic drift underscores the presumption of endogamy –which in turn augments physiognomic differences—and of which the Jews have long been accused.

Therefore despite the febrile imaginings of many anti-Semites, the common descent of Jews throughout the world is not seriously in dispute. In the end all modern technology has done is catch up with the tradition and folklore. Hitchens, in his disdain for theism, feels instead nothing but derision for tradition, no doubt because his atheism demands it. Hence his insistent acceptance of the gradualist, heterogeneous origin of the Israelite people in the first millennium before Christ.

Think about it: if Hitchens is wrong and the Jews are who they say they are, then this raises unsettling questions about the impetus that compelled them to set themselves apart throughout their history. This begs a further question: why, especially, since it often was not in their national interest to do so? Indeed, the entire history of the Jewish people can be characterized on one level as one long, studied fight to resist assimilation, often against great odds and against people to whom they were culturally inferior. In addition, if the revisionist narrative of natural, heterogeneous growth is false, then what driving force compelled the Jews to view themselves as a people apart? The Bible tells us that this was the command of God, who spoke through His prophets. The improbability of the revisionist position clearly demands that we look at the reality of revelation, something that Hitchens and the other New Atheists cannot do.

The History of God

It is my contention that what exercises Hitchens and others like him is that the Jews are by their very existence as a nation evidence of divine providence, quite literally God working in history. The history of the Jews is more than a mere metaphor for the history of monotheism (though it is certainly that as well). Unlike the pagans whom they displaced in Canaan, the Israelite nation in its essence, its culture, and even religious taboos, created a whole different way of looking at the universe. For these people, life had meaning, history had a purpose –time was linear, not cyclical. This is not natural in the sense that Yahwism doesn’t conform to nature as it was then understood.

The peculiarities did not stop there. Their creation narrative was singular in that it established the fact that Yahweh, their God, actually spoke the universe into existence. For most pagans, the universe was eternal and their gods nothing more than primal forces of nature who somehow arose out of the elements of nature. Living with such expectations, Yahweh could not have been a mere tribal deity, but literally the God of gods. This certainly was unsettling to the Israelites who wanted nothing to do with the other nations; to their neighbors such presumption was nothing less than a cause for undying enmity. In any event, the exclusivity which Yahwism demanded from the Israelites mandated the exclusivity which they practiced. On a materialist level this leads to the unfortunate conclusion that Judaism is nothing less than a type of racialism. Indeed, according to some Darwinists, Judaism is nothing more than an evolutionary imperative which allows Semites to displace and overtake host populations.xvi

The Prophet Jonah being thrown into the Sea. Catacomb of Saint Peter and Saint Marcellino, Rome, Itally, (4th century?).

Unless one is committed to materialism (which Darwinian naturalism requires), then we can confidently state that this exclusivity is not something that the Israelites chose for themselves. Even with the Temple cult firmly in place, they constantly relapsed into paganism, often due to the influence of the indigenous population which they conquered. Once their kingdom was destroyed and they were exiled to Babylon, they hoped that by retreating inward, then their dedication to Yahweh would somehow protect them as a nation and prevent them from paganism. Hence the post-exilic disdain for political nationhood and reliance instead upon the protection of Yahweh alone. Paradoxically, this led to a fundamental dichotomy in that if Yahweh were truly the only God, then He could not by rights be confined only to their race. And yet the evolution of monotheism took a decidedly tribal detour during this time, in which the Jews believed that Yahweh was indeed a God only for them. The prophet Jonah even thought that he could escape His dictates if he took off for Iberia, where he believed that the God of Israel had no power. (This view of Yahweh as the god of a people or place is more correctly called

henotheism or

monolatry.) Unfortunately for Jonah, he soon learned that God’s writ extended to the whole world, not just Palestine. Therefore, Jonah’s mission to the Ninevites , urging them to repentance was logical, even if he himself see the logic of it. There was no room for error: if Jonah failed, or if the Ninevites rejected his preaching, then they risked utter destruction. The dire nature of his mission presupposed the universality of God on several levels, not the least of which was that concern for the Ninevites was as vital to Yahweh as His concern for the Hebrews.

Although this was certainly troubling to Jonah, we can perhaps see why this narrative would be upsetting to the non-Jews who increasingly came to resent the presumption of the Jews, a nation of little accomplishment by way of architecture, culture, or political institutions. Hence the ancient, almost Darwinian imperative that seems to drive anti-Semitism; an impulse by the way, which predates the Church as we can see by the violent interaction between the Greeks and Jews during classical antiquity. Quite simply, the Jews are not only a metaphor for an eternal God, but living proof that this God works in the universe and demands adherence to timeless moral imperatives.

This rather elevated view that the Jews had for themselves was not one that was borne lightly. Indeed, it was just as upsetting to them as well as to their enemies. Why? Perhaps we can answer this question by restating the logical implications of true monotheism: if Yahweh was the God of the universe, then they could not reasonably keep God to themselves. True monotheism therefore demanded an exacting witness based on moral rectitude which was reinforced by the taboos normally associated with the Mosaic Law –taboos incidentally which were reinforced by the generous application of the death penalty. This inadvertently led to a type of evangelism, in which gentiles who had become disgusted with the mores of paganism eagerly responded to. Be that as it may, this was something that never before existed. The problems were intractable: how does one nation evangelize other nations? By what right did one nation feel that they had to convert other nations to their religion? This was simply unheard of. The Jews of the inter-testamental period certainly didn’t know how. And for our purposes, it’s not necessary to catalogue their efforts, many of which resulted in false starts, forced conversions (of Canaanites to Judaism), and philosophical disputations that all-too-often resulted in the acceptance of Hellenistic concepts. The one Jew who did understand that the God of Israel was universal and that His Temple was a house of prayer for all nations was killed for His efforts.

This is not insignificant. It is difficult to imagine in an anthropological sense which came first: the hundreds of cultural taboos of the Mosaic code or the universality of Yahwism. The Old Testament of course tells its own story of how this all came about. As much as Hitchens may not like it, he cannot seriously denigrate the fact of Yahwism and its activity upon the Israelites and their subsequent influence upon humanity. It is profound, so profound in fact, that it is nothing less than the very history of human civilization. Here, in a little area of the world, on the barren edge of the world’s first civilization, an insignificant, semi-nomadic, and savage group of tribesmen of no great accomplishment, chose somehow to segregate themselves from their pagan neighbors and forge a national consensus devoted to a singular, jealous Deity who demanded that they view the world in a way that no other group of people could conceive. The Israelites alone among all nations broke free of the iron hand of fate which governed all societies at that time. For them, time was linear, it had a purpose. Life had consequences, either in this world or the next. For the pagans an iron fate governed all; there was no meaning —and certainly no hope—prayer was merely ritualized bribery.

Not even the Greeks, for all their sheer brilliance could break the bonds of a cruel fate which nature had imposed on them. Despite their devotion to rationality and philosophy, Greek civilization invariably reverted to the prevailing paganism. The astronomy of Anaxogoras devolved into astrology; the science of Aristotle into alchemy; and the philosophy of Socrates into sophistry. The wise men of the Greeks, who came up with philosophy as a way of giving some meaning to the ubiquitous despair of paganism were the exception in Greece, not the rule.

Mars Hill (Areopagus), where the Apostle Paul addressed the Athenian philosophers (Acts 17).

It was not for want of trying however. Thoughtful Greeks of the post-Socratic period came to question the validity of the Olympian pantheon. Why worship beings that were no better than flawed humans albeit on an immortal, superhuman scale? For some of these rationalists, there had to be a supreme being, eternally existent, one who was just in His essence, not merely powerful. Otherwise, justice had no meaning. This was the concept behind the “unknown god” that Paul preached to the Athenians about on Mars Hill (Acts 17). Think of it: in a boisterous, cosmopolitan city like Athens, the intellectual capital of the Roman Empire, a group of disgruntled and questioning men sought permission from the city fathers in order to erect an altar to this unknown god, on a site in which the supreme court of Athens met to deliberate the great events of the day. Yet for all their brilliance and erudition, the Greeks could only, just barely, peer beyond the veil and discern the idea of true monotheism. Try as they might, they couldn’t let go of their own heroic pretensions. How can a God become a servant and die the horrible death of a criminal for all men—even barbarians even no less? The Greeks never believed that all men were deserving of equality, nor did they worry about concepts such as salvation. That the high priest of the Jews had to go into their national temple and offer sacrifice to God on behalf of the sins of the entire nation was incomprehensible. For

all men, even servants? And what is sin? How can it cut off man from God? (After all, the gods themselves engage in sin, therefore to the Greeks there really couldn’t be any such a thing as sin, just loss of virtue, which marked a man for life.)

Instead, it was a nation of semi-nomadic Semites whose peculiarities were legend, who were able to view their God as a God for all men, even for the despised of the world. Such a concept could only arise from revelation, an uncomfortable prospect for Hitchens whose virulent anti-theism cannot brook such a prospect. Regardless, the Jews certainly believed in revelation. Their nation began with the Exodus and their law was codified by the revelation on Sinai. Even their most powerful kings were brought to heel by renegades who claimed to speak for Yahweh. Quite simply, the taboos of the Mosaic covenant were the first in history to take into account the very concept of sin and its debilitating effects on the people as a whole. Sacrifice was not offered to appease God, but to atone for the sins of the people. Outside of this ethos, there is no way that the prophetic corpus makes any sense. Leaving aside this theological view of history and concentrating instead on a rationalist view, there is nothing in the historical achievements of the Israelite people—meager as they were—that would lead us to believe that they could formulate such concepts on their own.

And if there is no God, then why did the Israelites alone among all the nations of the world develop such concepts as sin, atonement, and moral rectitude?

Is the Holocaust also a Fable?

Hitchens is unaware of how perilous his naivete is, how it plays into the hands of other revisionists at this point. His belief-system is based in part on a superficial understanding of archaeology, but given his sanction, its logic can be turned to nefarious purposes. Consider: if there is no evidence for the Exodus, and if the Jews are a made-up people of no common origin, then why must one believe in the Holocaust? To be sure, the folk-memory for the Holocaust is vast. In addition, it occurred within living memory. Yet like the Exodus, revisionists have been able to pour much cold water on the particulars of that event to an unsettling extent. Some have gone so far as to examine the physical structures of Auschwitz, Dachau, and Buchenwald that remain and come to the conclusion that although mass murders certainly took place there, the limited physical space, the paucity of roads and railways leading to them, and the overstretched German war effort in general made it unlikely that upwards of twelve million people could have been killed in the concentration camps, of which six million were Jews and half a million Gypsies. Instead much smaller numbers are usually proffered: in the range of a quarter of a million to 2 million at the outside.

The gates of Dachau

Certainly Hitchens would bristle at such a comparison. Unfortunately, in watching Hitchens argue against the Exodus, one can see an uncanny (if unwitting) resemblance in the argumentation of many Holocaust deniers. In both cases, the reliance on historical reductionism is paramount. A doubt raised here, an event discounted there, is often all that is necessary to throw dust on a cherished narrative. Hitchens himself is guilty of whitewashing tyrants who tried to eradicate Judaism. He only turned against Saddam Hussein when the latter chose to embrace Islamofascism, otherwise, he championed this brute during the First Gulf War which took place in 1991. Saddam’s previous depredations were seemingly of no consequence, including the complete eradication of the Jewish presence within Iraq.

xvii This is of a piece with his fawning adulation of Antiochus, the Greco-Syrian king who tried to abolish all vestiges of Judaism some twenty-three centuries ago (as noted earlier). To put not too fine a point on it, the fact that he goes on to regret the fact that the Jews refused to succumb to Antiochus’ tyranny calls into mind his mental balance.

xviii To my mind this is as reprehensible as reading the diatribes of Holocaust-deniers who often refer to a more recent tyrant as “Adolf Hitler of blessed memory.”

The bad faith displayed by most Holocaust deniers is apparent. Many are haters, pure and simple. Others (mostly Arabs who are Semites themselves), bear an animus to the state of Israel, which they feel with some justification is a creation to assuage the guilt of the West in its treatment of the European Jewry. Some of the more virulent anti-Semites believe that the entire narrative was created out of whole cloth in order to give rise to the necessity for the Jewish state in the first place. And of course, it wasn’t really Jews who were killed there but Khazars. The incoherence of this position can be best summed up by the witticism leveled against the present Islamofascist regime of Iran: “The Holocaust never happened, now kindly ignore us as we prepare for the next one.”

Is Hitchens is an anti-Semite? Certainly he is not a Holocaust denier. That being said, when it comes to theism he uses the same type of bad faith as the assorted cretins that constitute the vast majority of anti-Semites the world over. Of this there can be no doubt. Even when it comes to Judaism his words provide cover to anti-Semites. Consider this particular diatribe:

…Judaism is not just one more religion, but in its way the root of religious evil. Without the stern, joyless rabbis and their 613 dour prohibitions, we might have avoided the whole nightmare of the Old Testament, and the brutal, crude wrenching of that into prophecy-derived Christianity, and the later plagiarism and mutation of Judaism and Christianity into the various rival forms of Islam.xix

And of course his facile dismissal of the Old Testament and his inability to see that the narrative of Israel –which is the story of God working in space and time—proves to my mind that he can’t see it, or won’t see it. Other revisionists certainly see this. Consider this statement from Finkelstein, who writes that the story of the Bible is radically unlike the royal sagas and epic myths of the other nations. What is different about the Old Testament is that,

…It offers a complex yet clear vision of why history has unfolded for the people of Israel –and indeed the entire world—in a pattern directly connected to demands and promises of God. The people of Israel are the central actors in this drama. Their behavior and adherence to God’s commandments determine the direction in which history will flow. It is up to the people of Israel…to determine the fate of the world.

Unfortunately, such laudatory words about the Bible and the Jews are anathema to Hitchens. For Hitchens his lodestar is the uber-rationalism of Socrates, the alleged “founder of his school” of skepticism. In his eyes, it was Athens, not Jerusalem, rationalism, not revelation which made scientific inquiry possible. Unfortunately, even here, Hitchens’ understanding of history is flawed. To be sure it was the West where science arose, but not in the Academy of Plato or the Lycaeum of Aristotle; it was instead in the monasteries of the Franciscan Order of the High Middle Ages that that the scientific method was first proposed, in the intermissions between the various liturgical offices while Gregorian hymns were being chanted in the background. It was the synthesis of Athens and Jerusalem which was found only in Christendom that made the Enlightenment—Hitchens’ golden age—possible.

In the pell-mell rush to demean the Bible and its moral code, Hitchens doesn’t realize that he won’t able to have his cake and eat it too. His admirable humanism, even his tenacious moralism, is a direct consequence of the prophetic corpus of the Old Testament. There were no Hebrew philosophers and no Socratic dialogue in Israel or Judah. There was no natural imperative which called the ancient Hebrews to view all of their people as being equally sons of God. But there was morality, and this was given to the prophets by God. The story of Israel is the story of human civilization and the morality which makes civilization possible. As admirable as Athens was, it could never spread its gospel of reason past the Greek world. Its own civilization could not withstand immorality and it fell to the barbarians. Had it not been for the Jews, then paganism would be the order of the day. Because God exists, and because the Jews strove to follow His commandments (however imperfectly), mankind was redeemed from the iron grip of a remorseless fate. The miraculous trumped the magical and moral conscience triumphed for all time.

If Hitchens strives to maintain his rigid adherence to belief in good and evil, then he cannot logically do so based on Darwinism or any such materialist presuppositions. The very concepts themselves arise outside the physical order itself. They presuppose transcendence. The murderous rage of the anti-Semite is the revenge of pagan nature against Yahweh, who is not a force of nature but the Creator of it. The very existence of the Jew is physical proof of the God of Israel and that He works in space and time. This of course is not the animating principle of the New Atheism but it will be the murderous reality of the real atheists, whose materialist instincts see Hitchens’ moralism for what it is: an illogical conceit that cannot withstand the inevitable lex talionis that governs nature and for which they yearn.

The irony is palpable: Hitchens’ anti-Judaic diatribes may yet prepare the way for another Holocaust. And the moralism to which he subscribes will prove to be thin gruel indeed to those who hunger for reasons to fight such a horrible outcome.

ENDNOTES

i. Benjamin Kerstein, “Christopher Hitchens’s Jewish Problem,” (Dec 13, 2010, www.jewishideasdaily.com).

ii. Ian Wilson, Jesus: The Evidence (San Francisco: Harper & Row, 1984), p 51.

iii. Nov 18, 2010, Prestonwood Baptist Church, Plano, Texas. “Debate with Bill Dembski.”

iv. Israel Finkelstein and Neal Asher Silberman, The Bible Unearthed: Archaeology’s New Vision of Ancient Israel and the Origin of Its Sacred Texts (Touchstone: New York, 2001).

v. Ibid. p 65.

vi. A good place to start would be The Dead Sea Scrolls in History, edited by Herschel Schanks (Puttnam: New York, 1977).

vii. Op. Cit.

viii. Ibid. pp 70-1.

ix. Ibid. p 68.

x. Ibid. p 69.

xi. Kerstein, Op cit.

xii. Dmitri Ouspensky, Byzantium and the Slavs, (Crestwood: SVS Press, 199), pp 40-42.

xiii. The field of genetic Judaism is a fertile one. For an introductory overview that is comprehensible to laymen, see for example Nicholas Wade, “New Light on Origins of Ashkenazi in Europe” (www.nytimes.com/2006/01/14/ science/14gene.html?pagewanted=print) and David Storobin, “Palestinian Genes Show Arab, Jewish, European, and Black-African Ancestry” (www.physicsforums.com /archive/index.php/t-58322.html).

xiv. The field of crypto-Judaism is a fascinating one. It appears that many historical figures (such as Christopher Columbus) may have had Jewish ancestry, at least in part. This also includes certain unsavory figures such as Fidel Castro, Mahmoud Ahmadinejad, and even Adolf Hitler.

xv. See for example the collected works of Kevin MacDonald, including The Culture of Critique: An Evolutionary Analsysis of Jewish Involvement in Twentieth-Century Intellectual and Political Movements (2001), Separation and Its Discontents: Toward an Evolutionary Theory of Anti-Semitism (2003), and A People that shall Dwell Apart: Judaism as a Group Evolutionary Strategy with Diaspora Peoples (1994). The primary thesis of MacDonald, an evolutionary psychologist, is that Judaism is an evolutionary survival mechanism that Jews have employed in order to dominate others by degrading host nations. Willis Carto, a founder of the Institute for Historical Review (the leading Holocaust denial institution), has stated essentially the same position as well. To be fair to MacDonald, he is no denialist nor does he self-describe himself as an anti-Semite, yet his Darwinian presuppositions force him to see not only the racialism inherent in his understanding of Judaism, but the inevitable backlash that such xenophobia and exclusivity causes –backlashes which take the form of pogroms and outright genocides. As such, MacDonald exonerates anti-Semitism by the same materialistic token that supposedly gives rise to Semitism in the first place.

xvi. As recently as the 1940s, Jews constituted almost 40 percent of the population of Baghdad.

xvii. Kerstein, Op cit. Kerstein goes up to the edge of the precipice and all but labels Hitchens an anti-Semite. Though I cannot agree, Hitchens has made it difficult for his admirers (of whom I am one) to defend his tactics at times. To put not too fine a point on it, Hitchens has all-too-often displayed a type of sophistry that goes out of its way to excuse the worst Nazi-philic excesses and outright racism as it is practiced by Palestinians. His defense of Voltaire (who was a notorious anti-Semite) is particularly troubling, but explains much in the way of his love for the Enlightenment of which Voltaire was a leading light.

xviii. Ibid.

George C. Michalopulos

George C Michalopulos, is a layman in the Orthodox Church in America. He was born in Tulsa, OK where he resides and works. George is active in Church affairs, having served as parish council president at Holy Trinity Greek Orthodox Church and as Senior Warden at Holy Apostles Orthodox Christian Church. Together with Deacon Ezra Ham, he wrote ‘American Orthodox Church: A History of Its Beginnings‘ (Regina Orthodox Press: 2003). He is married to Margaret and has two sons, Constantine and Michael.

The Corner | Nina Shea

The Corner | Nina Shea